Back in 2012, I was sitting with a group of fantasy writers at a conference in Seattle. Everyone had begun rolling off their favorite authors, and soon there were choruses of ah, yes and mmm. I just sat there silently with a glass of ice water. Most of my writing career had been a conscious detour around names like Robert Jordan, R.A. Salvatore, and Terry Brooks. But despite being the biggest cynic at any given table, I still love fantasy. So when everyone was finished gushing, I put in my two cents. And what I was saying, in effect, was “I don’t care where you get it. Get ‘Morrowind’ tattooed somewhere on your body.”

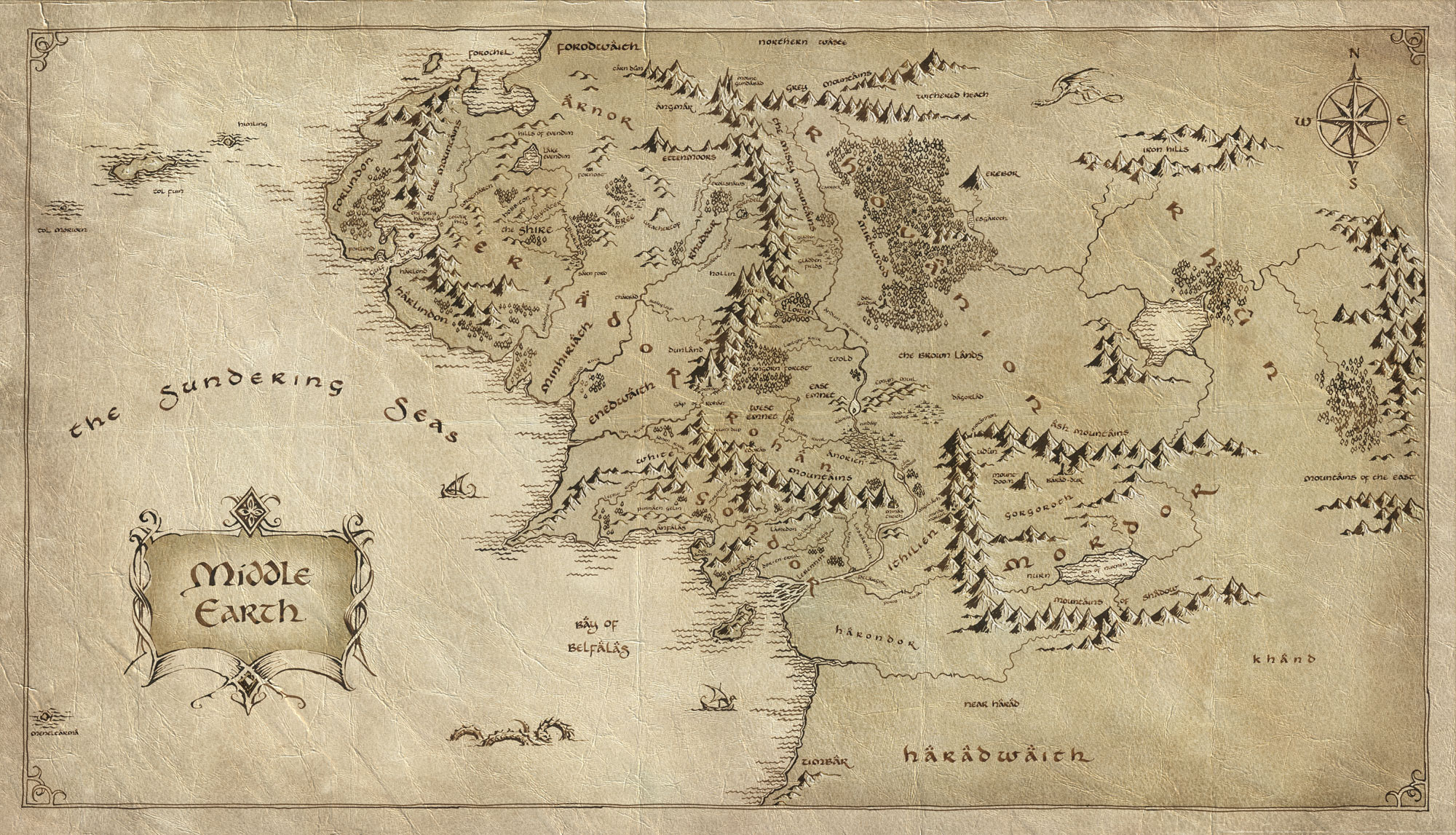

World-building is one of those things that set fantasy and sci-fi authors apart from any other writer: it asks for the skills of a cartographer, meteorologist, folklorist, geologist, linguist, political scientist, economist, and ecologist, then brings it all to bear on a story. Morrowind employed all of that to characterize the continent of Vvardenfell. And it’s one of the few pieces of fantasy I really believe in.

For those who haven’t heard of it, Morrowind was an award-winning, open-world fantasy game released in 2002 for PC and Xbox. There’s been a recent upsurge of people claiming that video games should be considered a form of art. I’m not here to argue for or against that. Over the course of my life, I’ve bought a little over a dozen video games, and I’ve only finished about three. But there’s a point where something brings so much to the table, so much imagination and depth, that it deserves to be studied. The greatest point in its favor, besides being a fully developed world, is that Morrowind avoids the conventions of the genre and reminds you that this is fantasy, where the horizons are endless. If you’re not a fan of video games, you don’t need to be. You just need a legal pad and a pen to take notes.

So let’s talk about world-building.

The geography of the continent of Vvardenfell is tremendously diverse, and right off the bat, that’s a good thing—mainstream fantasy is dominated by the shadow of medieval Europe: huge tracts of forest, grassy countryside, and snowy mountain ranges that conveniently divide kingdoms along their bases. The climate is almost always shades of England, except maybe an ‘exotic’ Caribbean tropic region or a ‘faraway’ Middle East or China analogue.

Vvardenfell, however, unifies a whole range of climates and landscapes into one cohesive setting. It’s a volcanic island with ash-blown badlands surrounding its mountain, wet jungles on the west coast, vast grazing lands in the northeast, and a fertile archipelago in the south. In each region, there’s a specific set of animals, landforms, and plants that characterize it, just like real biomes. In the Ascadian Isles archipelago, the tiny, scattered islands mean predatory, salmon-like slaughterfish and island-hopping, either by swimming or boat. In the long lava canyons around the titanic Red Mountain, ash storms can create white-out conditions, making it easy to get lost and even easier to be ambushed by the tribal Ashlanders (and the god-forsaken cliffracers).

All of this demonstrates that it’s possible to create a varied, fascinating landscape for your stories, giving your reader more than just backdrop, but immersion. Travelling through Vvardenfell was one of the main attractions of the game, and crossing the continent was a story all in itself: walking under mushroom trees and through wastelands of standing stones made you feel as if you were on an adventure. There was a sense of Vvardenfell’s desolation, danger, and beauty, and a good portion of your time could be spent just appreciating it all. This kind of care put into a setting ignites a reverence for the world and an investment in the story.

Geography also enhanced Morrowind’s culture: instead of making different regions into cookie-cutter cultural blocs, giving the Ascadian Isles people one token set of beliefs, the Bitter Coast people a totally different set, and so on, the whole continent had a strong sense of identity. The Dunmer, the elven residents of Vvardenfell, are the same curt, xenophobic, tradition-focused race regardless of where they live. Cultural diversity is fantastic in a setting, but it’s also interesting to see a single race adapt their way of life to different lanscapes and still retain their customs and heritage; it gives them depth and durability.

That being said, Morrowind is spiderwebbed with deep divisions: there are three Great Houses in Vvardenfell, representing three very different sides of the Dunmer people. House Telvanni, which controls the northeast part of the continent, is almost a rogue state: it annexes territory secretly and often abandons treaties when it suits them. Most of the power in the House is held by wizard-lords, who live in elaborate mushroom towers and hold huge slave populations. House Redoran is built around preserving the ancient Dunmer heritage, and heavily resembles samurai in their devotion to honor, proper behavior, and adherence to a warrior code. They are also the most pious House, with a close partnership with the Dunmer religion, the Tribunal Temple. House Hlaalu is an interesting beast: made up of the merchant class, the House has embraced a more pragmatic and tolerant view of other cultures because of their trading practices, but their facade masks close connections with the criminal underworld and the highly racist Camonna Tong gang.

The Great Houses offer an alternative to the usual plots of political intrigue. Instead of fighting over an emperor’s throne, the Houses are in conflict with one another over territory and resources. They are not separate countries; on the surface, all of them are loyal to Vvardenfell’s godking, Vivec. Outright war is never declared, trade is never cut off, and members of different houses are free to move through one another’s territories, but everyone on the street knows that spying, closed-door negotiations, and even covert raids are taking place on a regular basis. Expansion is the prize.

If tensions rise too high, the Houses have a ritualized form of warfare: they call on an impartial organization of assassins, called the Morag Tong, to kill members of other Houses. The interesting thing is that this kind of murder is a legal and open practice. At the scene of an assassination, the Tong member can show an Honorable Writ to demonstrate that he is a legitimate combatant, and according to the rules of warfare, no one can punish or capture him.

What this adds up to is a highly diverse but coherent set of conflicts, contained within one continent and one people: the Dunmer have a shared history, a shared faith, and a shared homeland, but the Great Houses divide them along ideological, economic, and cultural lines. The best part is that the Houses are fighting for their constituents—it’s the common people’s interests and beliefs that drive them. The battles are over slavery, adherence to tradition, or settling new lands, so the politics and intrigue are more akin to a Malcolm X rally than a Richard the Third-style genealogy map.

Then there’s the economy. Economics is not money. It’s what people are eating, how people are employed, what people make their houses out of, who makes the boats, and who rises to power. It all depends on the flow of materials, educated craftsmen, and influence. Every reader of Dune knows the old saying about the spice and the universe.

The economy of Morrowind can be broken down to four things: kwama, saltrice, mining and smuggling. Kwama are like giant domesticated ants, which live in extended burrows and produce eggs, which are then harvested and sold as one of the main foodstuffs of the continent. Saltrice is a common crop raised by farmers, and serves a purpose similar to flour. Mining consists of ebony, precious gems, and volcanic glass, all of which come from the volcanism of Red Mountain. Smuggling is endemic throughout the island, with coasts dotted by caves and secret docks, and offers a way to transport goods at lower prices. With these four elements alone, you have a blueprint of Dunmer society.

People need saltrice and kwama to survive. “Miners” need to be employed to work in the kwama tunnels, and farmers need land to raise saltrice. So cities like Balmora grow up near the kwama mines, where many people are employed as miners. Slave plantations are created for saltrice, creating a whole tradition of slavery in the Dunmer culture. Beasts of burden, the dinosaur-like guar, become domesticated to transport these goods, which mean there are guar breeders and guar thieves. Meanwhile, the families who control the ebony mines are growing rich from exporting it, and with their money they’re funding their Houses, which use the money to arm their soldiers and improve their cities. Because of this, Houses become dependent on the expansion of their mines. At the same time, smugglers are importing and exporting goods underneath the nose of the government, creating a whole underground market of low-cost goods for the poorer villages and fostering criminal elements near the coasts. Anti-government sentiments are created, and the coast becomes an anarchical Wild West. Every world should have an economy this dynamic, this exciting. All it takes is some farmers, miners, and smugglers.

But there’s something even more exciting: religion. Morrowind’s Tribunal Temple is a great model for a theocratic state and a living religion: Vvardenfell is ruled by the Tribunal, three earthly deities who have delivered the Dunmer people from demons, droughts, and invading races and live in giant palaces throughout the land. There’s a whole series of books and shrines inside the game that detail the chief god Vivec’s historic travels and saintly acts, which range from reviving the Dunmer with his tears after horrible ash storms to working as a beast of burden in a field to help a poor farmer. He and his Tribunal are living heroes to the Dunmer, and serve as the de facto rulers of the continent.

What makes this unique is that this religion lies at the heart of the Dunmer: their history is tied up in it, their heritage is tied up in it, and the rule of Vivec is an earthly one. Vvardenfell is, to the eyes of the Dunmer, the living kingdom of God. It’s also a land where the divine enemies of the Tribunal, collectively referred to as the House of Troubles, spawn monsters, summon earthquakes, and spread madness, so the Tribunal Temple is also a holy army and a bulwark against destruction and chaos. Religion in most fantasy settings is usually some reflection of the Christian religion: unseen divine powers surrounded by a far-off and highly elaborate Church. In the common lives of people in those settings, religion is either absent or an oddity that sets someone apart. In Vvardenfell, the Dunmer religion is woven into the communities and the daily life of its people, in the same ways that make religions like Islam or Buddhism so fascinating. It’s also part of a war for their survival, their lands, and their way of life, fought against demonic forces and foreign races.

But all of this barely scratches the surface. Morrowind had, by far, one of the most alien fantasy settings I’ve ever seen: giant, magical floating jellyfish were raised for leather, men riding twenty-foot-tall fleas ferried you around the continent, the Redoran capital was built inside the carapace of a huge, extinct species of crab, and the scattered, bizarre Daedric ruins were the epitome of H.P. Lovecraft’s vision of non-Euclidean architecture, complete with unpronounceable names like “Ashalmimilkala.” It was wildly imaginative, but all of it had such a strong internal logic that it made the mushroom trees and jellyfish leather seem natural. Everything was so tightly woven that you couldn’t help but believe in it. So, if you’re committed to building an engaging, unique world for your stories, look it up. The more you learn, the more you can hear it whispering “This is what you came for. This is fantasy.”

And that Morrowind tattoo starts making more and more sense.

THE Three Body Problem by Cixin Liu

THE Three Body Problem by Cixin Liu 7 Different Ways Fantasy Has Used Language as Magic

7 Different Ways Fantasy Has Used Language as Magic No Mother Tongue: Language in the world of Magic

No Mother Tongue: Language in the world of Magic