Hail. I am I, Don Quixote.

The meaning of the story of Don Quixote changes depending on the teller, but it begins with Alonso Quixano, an old man who reads so many stories about knights and dragons that he loses his ability to distinguish between fiction and reality. In his delirium, he sets out as Don Quixote, knight-errant.

There are some windmills in there, too.

What a lot of people don’t realize is that Don Quixote, upon its publication, signaled the death of the chivalric romance, the same books that told tales of knights and magicians, giants, chivalry, and virtue. Don Quixote was a clever, vicious satire in addition to being one of the greatest novels of all time, and its rise put the chivalric romance out of fashion. It also started a debate: what effect do books have on people’s minds?

I was watching a video by Evan Puschak about worldbuilding in fantasy yesterday. In it, he makes a couple of suggestions about the nature of fantasy novels, world-building, and the relationship between authors and readers. These, I think, were his main points:

- Reading is not the author telling the reader a story—reading is a game in which the author makes implications and the reader uses their interpretive toolbox to create their own interpretation of the story.

- Worldbuilding in fantasy novels today is largely based on a passive mindset within the reader because the reader is dependent on the author for the truth about their world.

- Fantasy readers’ intense desire to learn about an author’s fantasy world is dangerous because that obsession acclimates readers to passively accepting other forms of ‘worldbuilding,’ including political ideologies.

- Fantasy novels like Viriconium that challenge readers’ assumptions and make them question their preconceptions about literature and the world are valuable because they cause readers to abandon a passive mindset.

Evan’s video ends on the note that we should seek out impish, challenging books that don’t conform to our ideas about fantasy and make us question our relationship to the novel.

I agree with some of Evan’s points and I disagree with most, but it’s not really the points Evan makes in the video that I want to talk about. I want to talk about the ideas that lie beneath them, because those are the ideas that I really disagree with.

Running underneath Evan’s suggestions are concepts like the death of the author, Sausserean theories of symbol and language, sociology, Marxist literary criticism, and the Hegelian idea of the dialectic. I want to explain what these are, and what they mean to me when it comes to fantasy and writing.

YOU ARE ALONSO QUIXANO

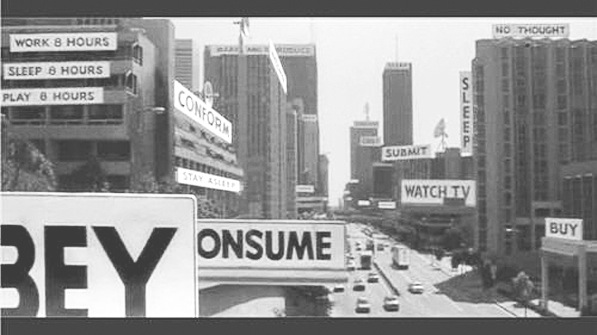

When Evan says worldbuilding is dangerous, he uses a line of thought that’s influenced by sociology and Marxist literary criticism, which views humans as objects that are primarily shaped by their society and culture, constantly subject to different ‘ideologies.’ Ideologies are sets of ideas meant to manipulate people into certain behaviors, and are generated by those in power to control the populace. Evan compares George R.R. Martin’s worldbuilding to the commercial and political ‘worldbuilding’ of L’oreal and Fox News, and claims that if you readily accept the former kind, it’s easy to accept the latter.

The main idea of the video, which is subtitled the ‘perils of worldbuilding,’ isn’t about whether or not fantasy worldbuilding is the same as the commercials and commentary of shampoo companies and news networks—it’s about the Marxist idea that you, as a person, are solely the product of your society and culture, and that you are so vulnerable to be conditioned to accept certain ideas that worldbuilding in fantasy novels is dangerous to you. The books you read are acting on your subconscious, constantly rewriting your thoughts without your knowledge and guiding your decision-making in the future. Before you entertain the ideas in the video, you have to accept that premise.

FRODO LIVES, BUT GOD IS DEAD

Evan also shifts the definition of how a novel works in his video, claiming that a story is created through a reader’s interpretation of the author’s writing. This is different from what we usually expect the relationship between reader and author to be: the author comes up with an idea for a story and tries to convey it as best they can to the reader. Evan is substituting a model of reading that stems from a concept called “the death of the author,” in which the reader, not the author, is the person who decides the meaning of the story. The reader does this by looking at the story through any number of different lenses—these can be socio-political, religious, economic, or racial.

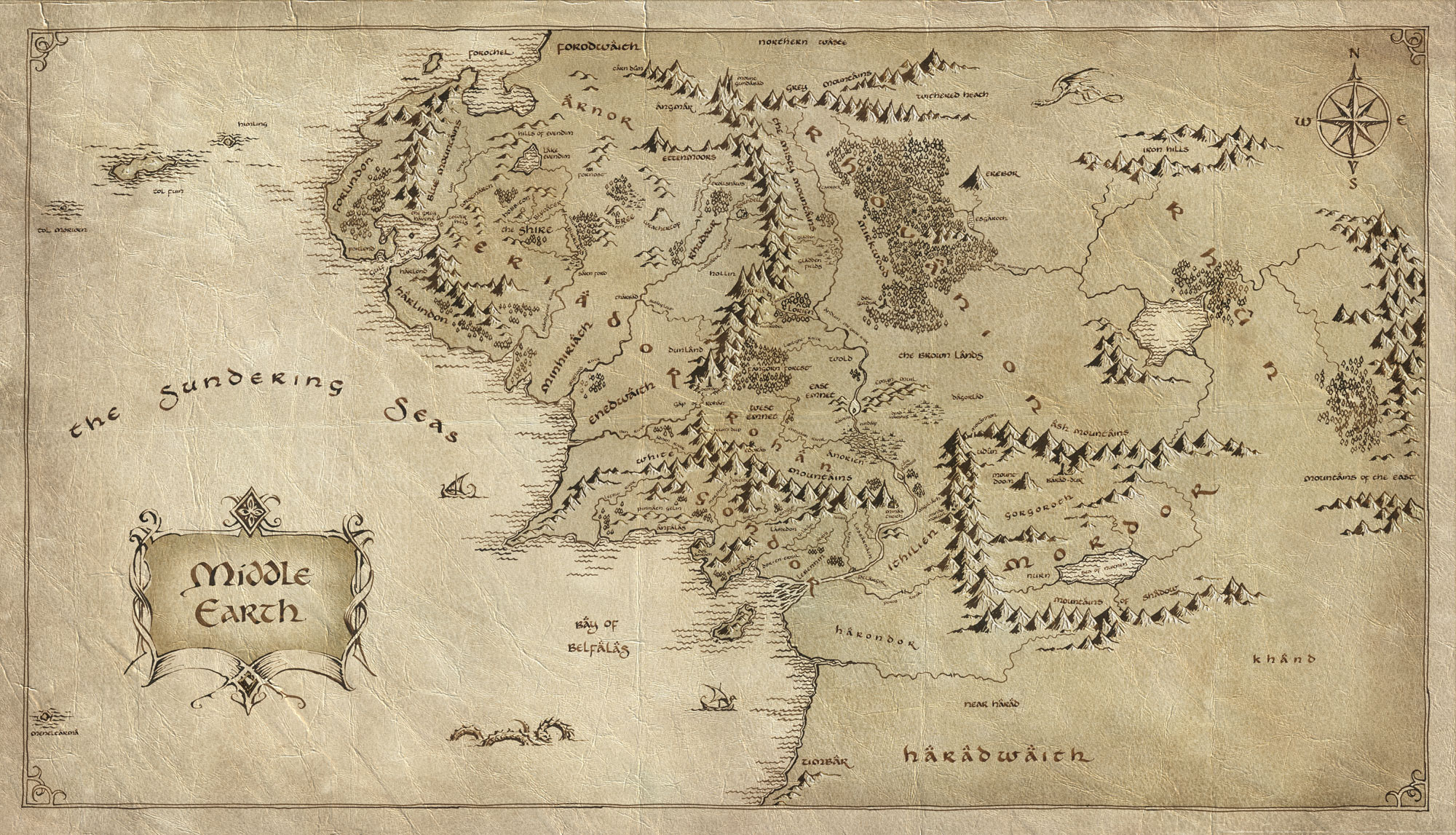

What Evan is finding problems with specifically, however, is worldbuilding within fantasy. It’s a corruption of the relationship between reader and text, he claims, to have a dimension of the story that is not up for interpretation—in this case, the geography, history, and magic of the fantasy world, which is all understood and explained solely by the author. That, to Evan and his theoretical background, is a problem.

This is because Evan’s body of literary theory, called critical theory, is also influenced by Friedrich Nietzsche, an existentialist philosopher who rejected any philosophies that claimed to have a monopoly on truth and morality, and instead claimed that we all must find own definition of morality and our own way to live our lives. One of Nietzsche’s famous claims was that God was dead, meaning that in this new, modern era, appeals to universal truths, like religion or Kant’s philosophy of deontology, had proven to be irreparable failures, and that we had entered a new era of unparalleled freedom, unbeholden to any external authorities.

This comes all the way back to authors being the source of truth about their own books. Evan and critical theory reject authors as being the final authority on their own works, because in their view, there is no such thing as ‘truth,’ only interpretations.

THE IMPOSSIBLE DREAM

Finally, Evan’s encouragement to seek out books that make us question our assumptions about fantasy and novels themselves (as well as his championing of Viriconium) comes from an idea called ‘the dialectic.’

The dialectic is a way to chart the growth and development of ideas, and begins with a thesis, or the proposal of an idea. Then a negative reaction comes, called the antithesis, which disagrees with the first idea. The two come into conflict, and create a synthesis, from which a new idea is taken. Then the process starts all over again. The dialectic, according to critical theory, should be a model for the way we live and think: everything we accept should be treated as a thesis to be questioned, negated, deconstructed, and rebuilt anew.

The directive to constantly challenge yourself and your preconceptions, to unsettle or overturn the established order, and especially to pursue books that do not conform to the usual structure of a novel comes from the idea of the dialectic. On the surface, this seems to be the essence of open-mindedness and the progressive ideal—question, debate, discover!—but the problem is that there is no goal or ideal that the dialectic is striving for. Every thesis must be attacked simply for being a thesis. More than that, we should not strive to find something true and eternal and constant—we should pursue constant change, never allowing ourselves to build a dogma. The dialectic is change for change’s sake–there is no utopia it’s trying to achieve, no final goal.

What is the goal of writing and reading, then? To deconstruct and question the definition of reading and writing, and build a new model. The cycle will then begin again. Like the dialectic itself, books and reading are not avenues to truth, catharsis, understanding, or meaning–they’re ends in themselves, to be explored, destroyed, and reconstructed.

In the mindset of the dialectic, it’s quixotic to believe in any kind of truth or any purpose to reading and writing beyond being an exercise in thesis and antithesis: everything is just grist for the mills.

MADDEST OF ALL

I wrote a manifesto for why I write a while ago. It starts like this:

“I don’t know if it’s a characteristic of this age or a sign that we’ve come to a fuller understanding of life, but nothing seems certain today. The more you pull the string of who you are, who you love, what you should do and why, the more string keeps coming. There has to be something solid to hold onto, something that’s undeniably true. And what I inevitably come back to is the knowledge that if we are all lost, we are lost together. Writing is a way to bring people solace by showing them that, ‘in the face of all aridity and disenchantment’, there is solace in each other and wonder in being alive.”

And it ends like this:

“I want my [stories] to soak into their mind until little black drops of it start dripping onto their soul. There’s too much in our hearts that never gets to see the light of day: terror, sorrow, joy, desperation, and wonder. When a story begins to awaken these feelings, it reminds the reader that, dear God, life has some sort of power running underneath all these crosswalks and Wednesdays and rent payments. It’s like waking up from a dream and seeing the world for the first time, unfurling in all its terrible and asymmetric beauty.”

Writing, to me, is about creating something that illuminates people’s lives. That comes from my belief that there are truths that can unite people, and some human condition that we share, and that I, as a person, can create stories that evoke that human condition. This belief stands in opposition to the philosophy that drives Evan’s assertions about fantasy writing and worldbuilding, and it goes against many of the critics who are trickling into the sci-fi and fantasy genre, many of whom are influenced in some way or another by critical theory.

This, for me, isn’t just a conversation about literary theory; this is a discussion about how we view the world and what guides our lives. That’s why I care. I’ve told my side, now it’s up to you to go out, read some more, think some more, and decide what you believe in.

I’ll end with a clip from Man of La Mancha, a movie that shows another side of Don Quixote, the novel that killed knights and magic. This scene shows a fictional Miguel Cervantes and his answer to why he writes.

Click the circular button below to Share this post.

Leave a Reply