Now we come to the real, meaty occultism that everyone’s looking for in their origami pyramids: Kabbalah. But, as J.R.R Tolkien found out when trying to research the Eddas, there’s a problem with learning about ancient mythology and the occult: the materials that have become the “official” accounts of both Kabbalah and Norse myths are usually heavily altered by later authors or totally made up for the purpose of gaining profit, cultists, and loose women. It’s this cross-millennial game of Telephone (more “Forgery and Revision”) that created the New Age movement, including Dion Fortune’s The Mystical Qabbalah.

So to understand the nuances of Kabbalah, you’d better be a Hebrew scholar with a doctorate in it. I’m not a Hebrew scholar, and I definitely don’t have a degree in medieval esotericism. I chose a much more practical, business-minded college degree (English). So I’m not an authority on the Sephiroth, I just play with its ideas.

Shaving it down to its most basic ideas, Kabbalah is a primarily Jewish philosophy that proposes a hidden, or “esoteric,” symmetry in the Universe based around Ein Sof, which is the embodiment of God, Creation, Truth, and Infinity. The practice of Kabbalah is meant to help practitioners learn to reconcile themselves with Ein Sof and learn the truth of their connection to all of creation. The concept of Ein Sof as Infinity was especially fitting for ANATMAN, since it brings together truth, the universe, and the metaphysical (and mathematical) concept of infinity, which, as I’ve talked about before, all seem to overlap in the search for enlightenment. Another fitting concept of Ein Sof is Kether, or unity and oneness. Ein Sof unites everything in itself: humanity, the universe, and God. There are no fundamental divisions between things, and the only thing that keeps you from recognizing this is ignorance, deception, and unholiness. Compare this to Part 1 and the description of enlightenment in Zen Buddhism:

“Enlightenment is embracing your own annihilation, because the truth is that “you” do not exist. “You” is no-self, no-soul. You are Void, because you are the universe, and the universe is Void. There are no divisions anywhere, no up or down, no day or night, and no division between life and death.”

No divisions, just unity. You and the universe. Kether in Kabbalah, like the Void in Zen Buddhism, can be thought of as a coin, with oneness and self-annihilation as different faces. Now, the recurring problem: enlightenment means the disappearance of all your desires, pleasures, fears and the person you call yourself. “You” have to die. Death is necessary for enlightenment. You either choose to die spiritually in enlightenment and reconcile yourself with eternity to be reborn, or you choose to die physically and succumb to time, old age, and constant change.

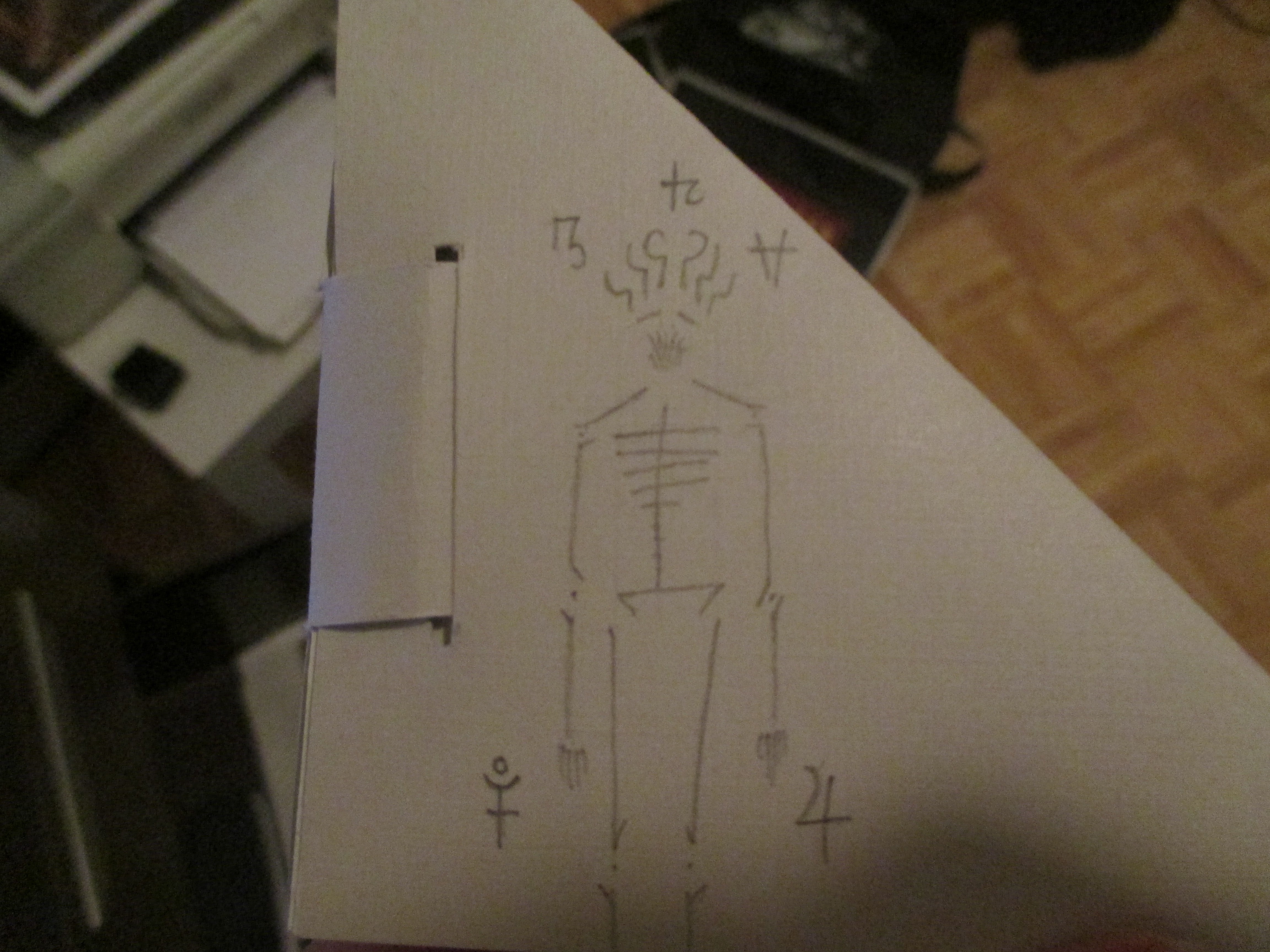

In Kabbalah, there is the Sephiroth, the Tree of Life and Knowledge, which is the ten-part route to Ein Sof, with Malkuth, or earthly existence, existing on the lowest branch of the Sephiroth. You can ascend the Tree or sit in Malkuth forever. In Buddhism, you would be thrown into the Wheel of Samsara again after death and be reincarnated, repeating life and death forever.

In Kabbalah, there is the Sephiroth, the Tree of Life and Knowledge, which is the ten-part route to Ein Sof, with Malkuth, or earthly existence, existing on the lowest branch of the Sephiroth. You can ascend the Tree or sit in Malkuth forever. In Buddhism, you would be thrown into the Wheel of Samsara again after death and be reincarnated, repeating life and death forever.

But what if there was another way, another path? A crack in the whole system of life and death, enlightenment and the universe? Anyone who found a way to escape the rules and unity of the universe would exist outside all rules and order. There would be a place outside of eternity.

And this is where the Qliphoth, the Kabbalah Tree of Death, comes in.

THE QLIPHOTH

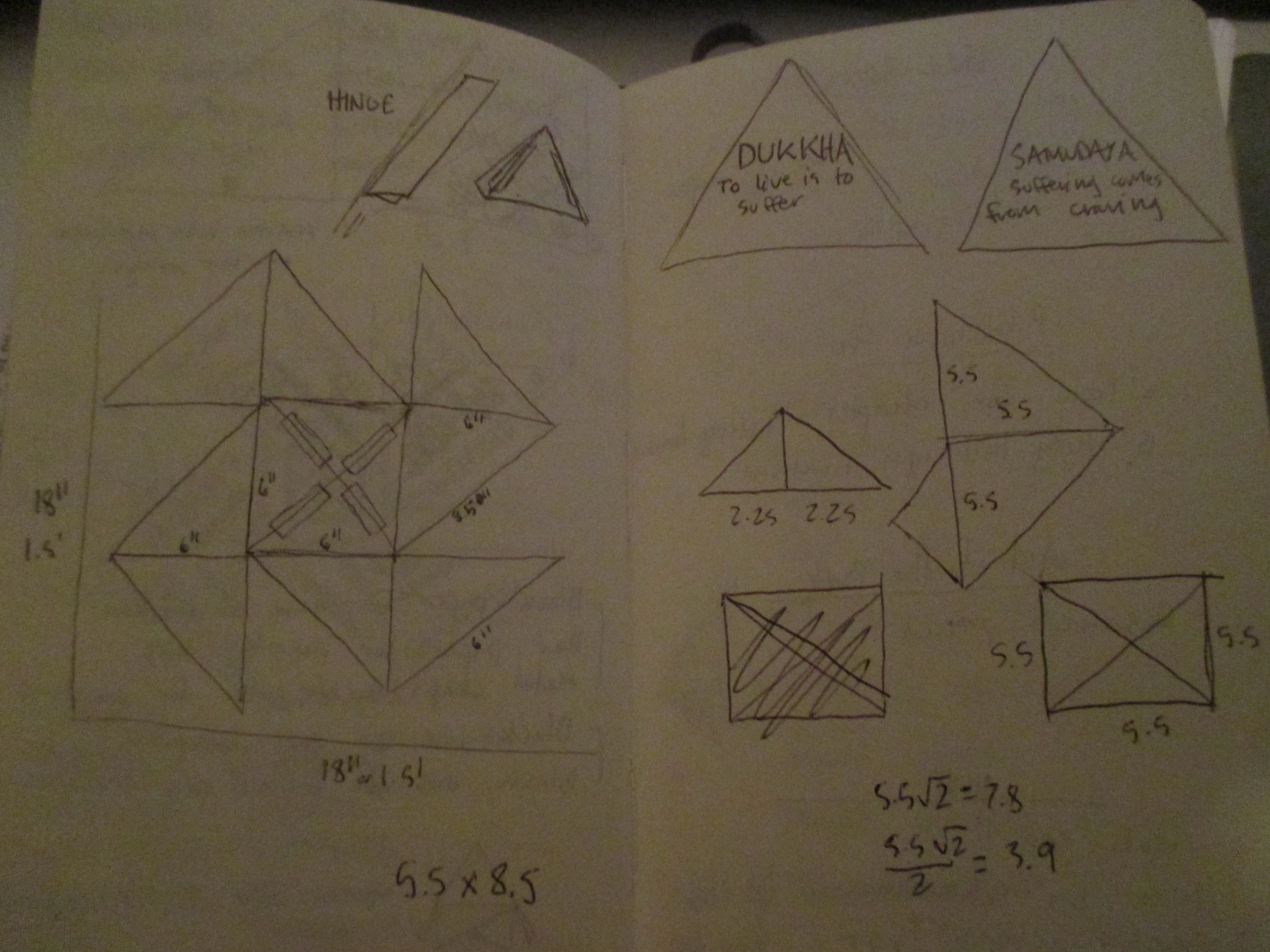

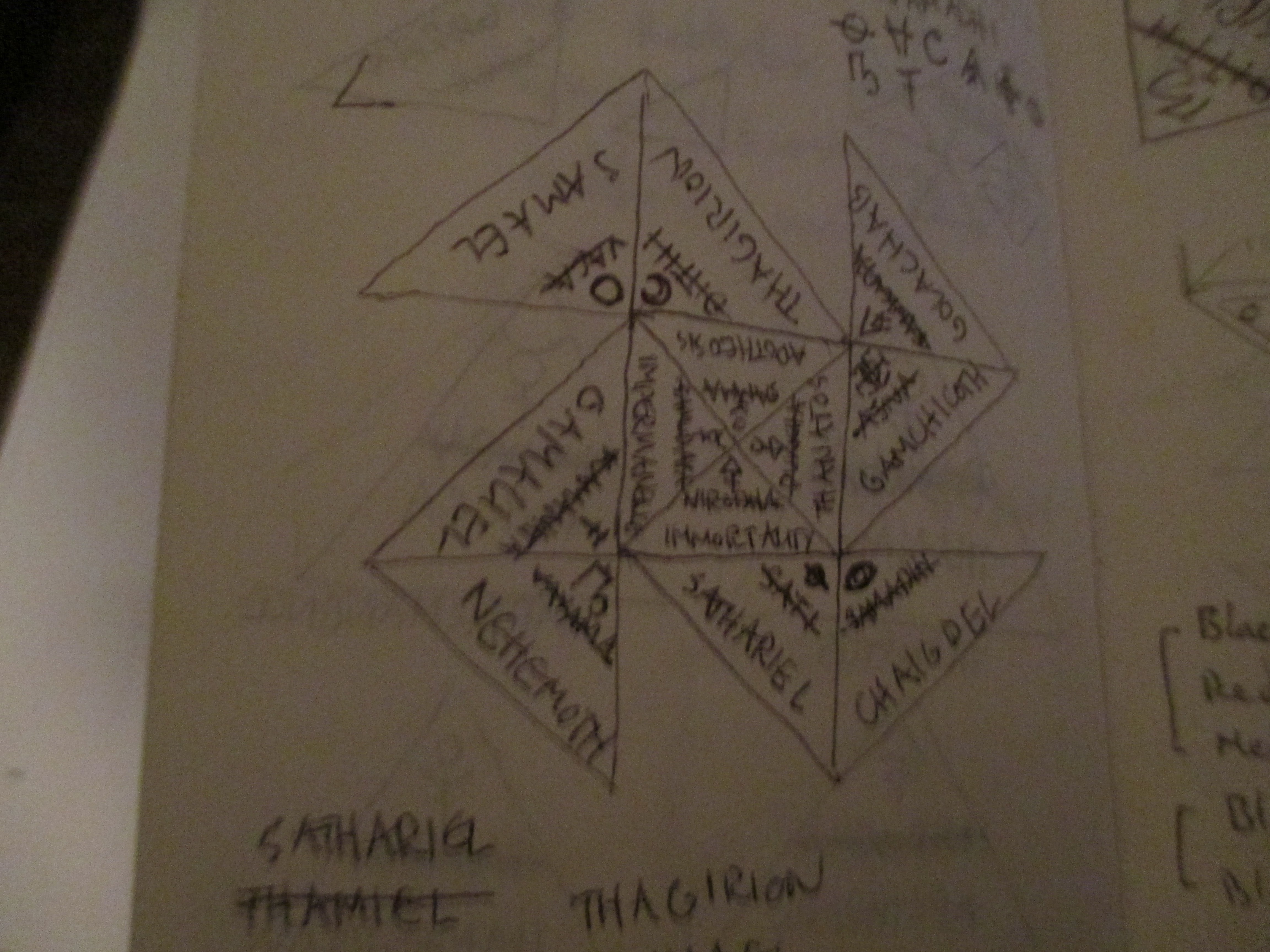

There exists an antithesis to the Sephiroth, and it’s called the Qliphoth. The Qliphoth is the universal structure by which the Truth of Ein Sof is perverted, twisted, and otherwise hidden. Each of the ten points of the Qliphoth represent the antithesis of its correlating sephirot in the Sephiroth, and two of the highest levels of the Qliphoth are Thamiel and Chaigdel, which oppose Kether and Chokmah, respectively. Thamiel represents division instead of unity, and Chokmah represents emptiness when there should be fullness, especially in the universal life-force.

(Take note of these two ideas, Chaigdel and Chokmah–they’re going to show up later, in fractal geometry, no less.)

The Qliphoth offers an alternative to the conscious choice of enlightenment and the unconscious choice of ignorance, at least in my conception of it. By choosing to follow the Qliphoth, you can place yourself at an infinite distance from Truth, God, and Eternity, and this is different from being unenlightened. You choose to be the antithesis of the Universe rather than the embodiment of it. This is the greatest perversion of enlightenment: knowing the nature of yourself and the universe, and rejecting your place in the grand unity of it all.

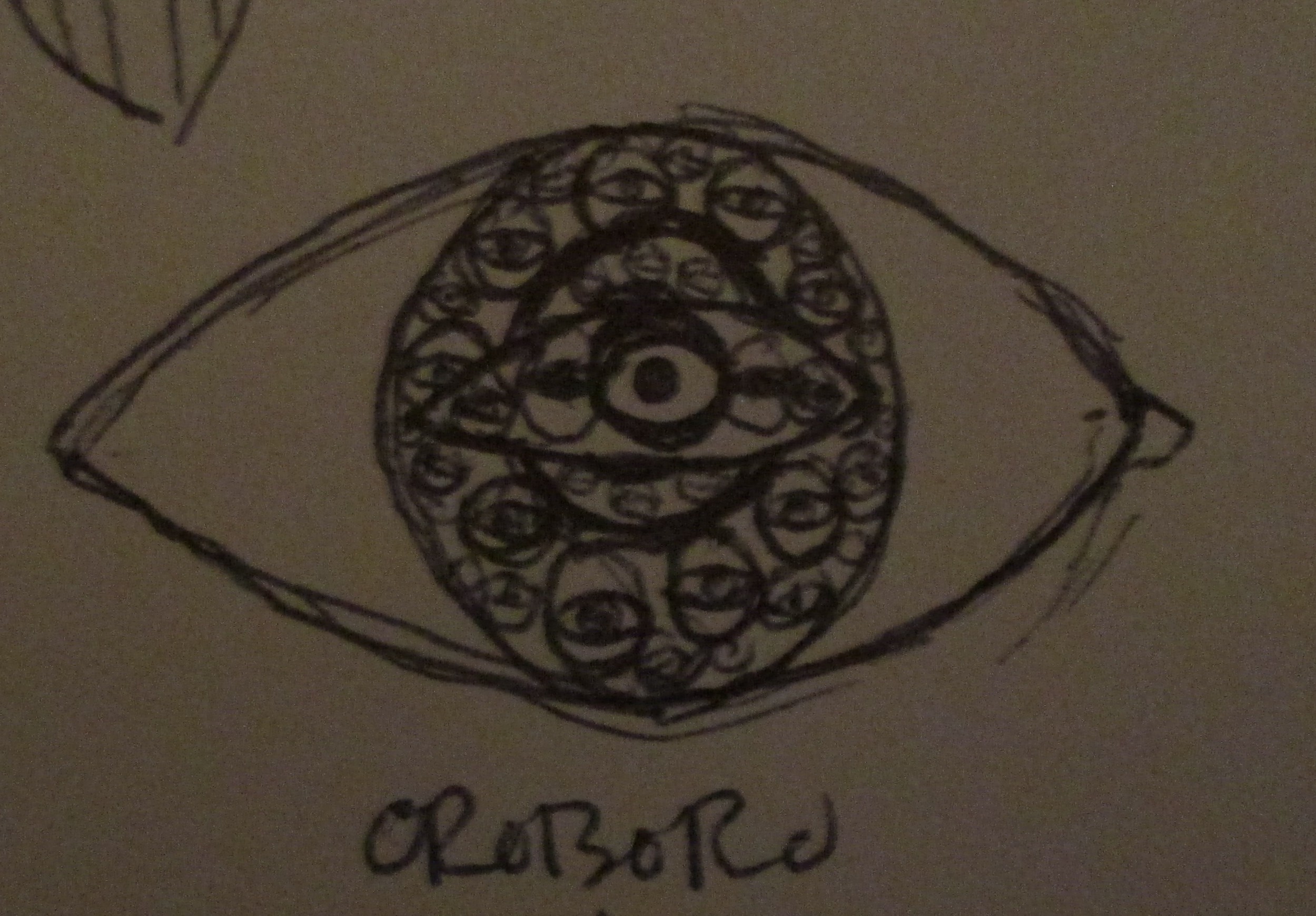

What kind of life would that be? If you’re not part of the grand scheme of creation, are you a creation unto yourself? A closed circuit? If you’re beyond creation and destruction, how can you exist? If you’re beyond life and death, what kind of power can sustain you?

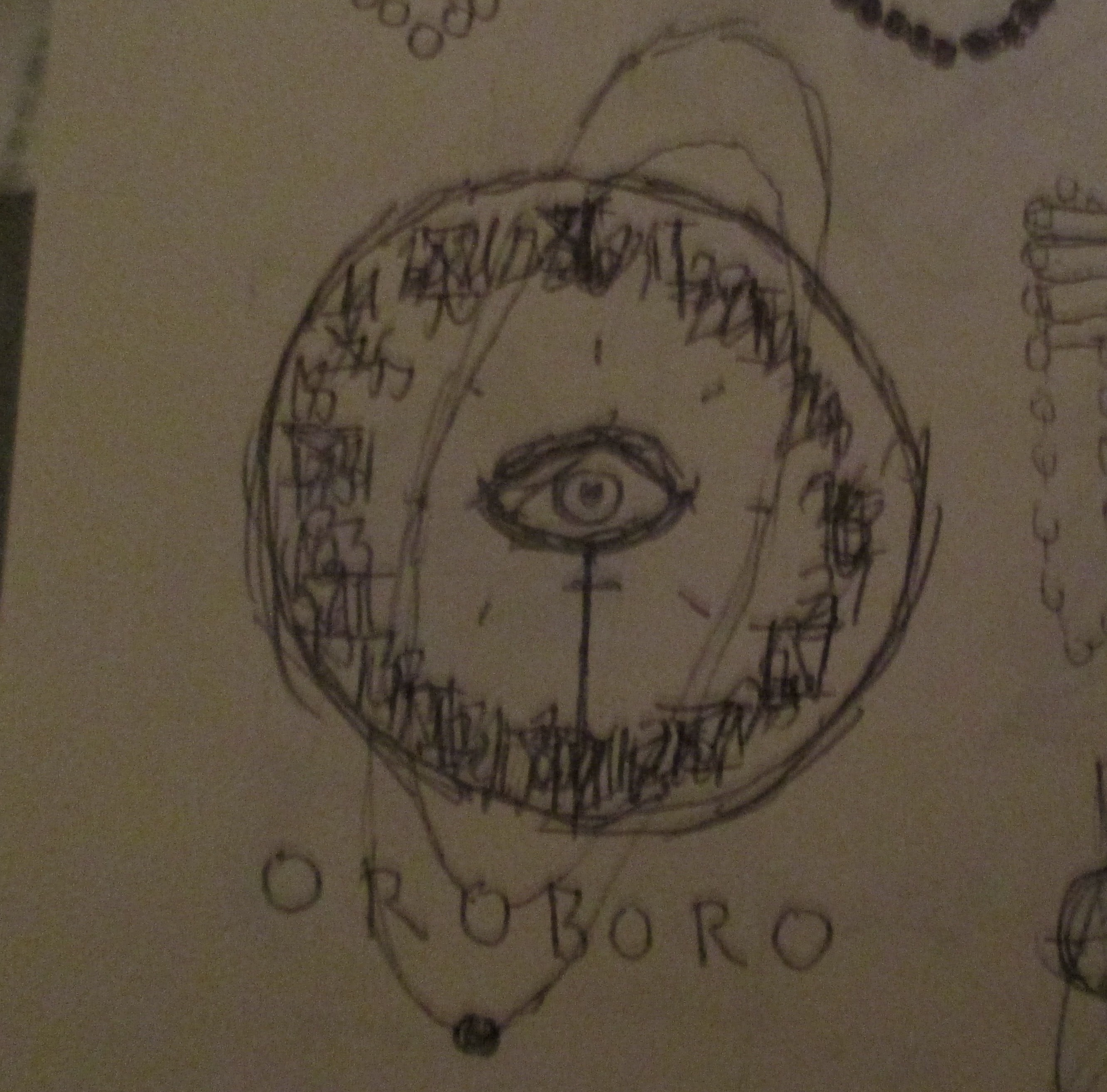

There is a name that sums up this kind of existence: Ouroboros, or the snake that eats itself.

Next up in Part 2: Oroboro and Fractals.

Click the circular button below to share.

that monks are supposed to meditate on. How can one hand clap? It is impossible. You’re supposed to give an answer. But you can’t answer. There is no answer, because the question itself is wrong. The lesson, if you can arrive at it through meditation, is that questions can be wrong, not just answers. This idea is called mu. And just like the question of one hand clapping, the question “Who are you?” is equally wrong, because everything you conceive of as “you” is wrong.

that monks are supposed to meditate on. How can one hand clap? It is impossible. You’re supposed to give an answer. But you can’t answer. There is no answer, because the question itself is wrong. The lesson, if you can arrive at it through meditation, is that questions can be wrong, not just answers. This idea is called mu. And just like the question of one hand clapping, the question “Who are you?” is equally wrong, because everything you conceive of as “you” is wrong.

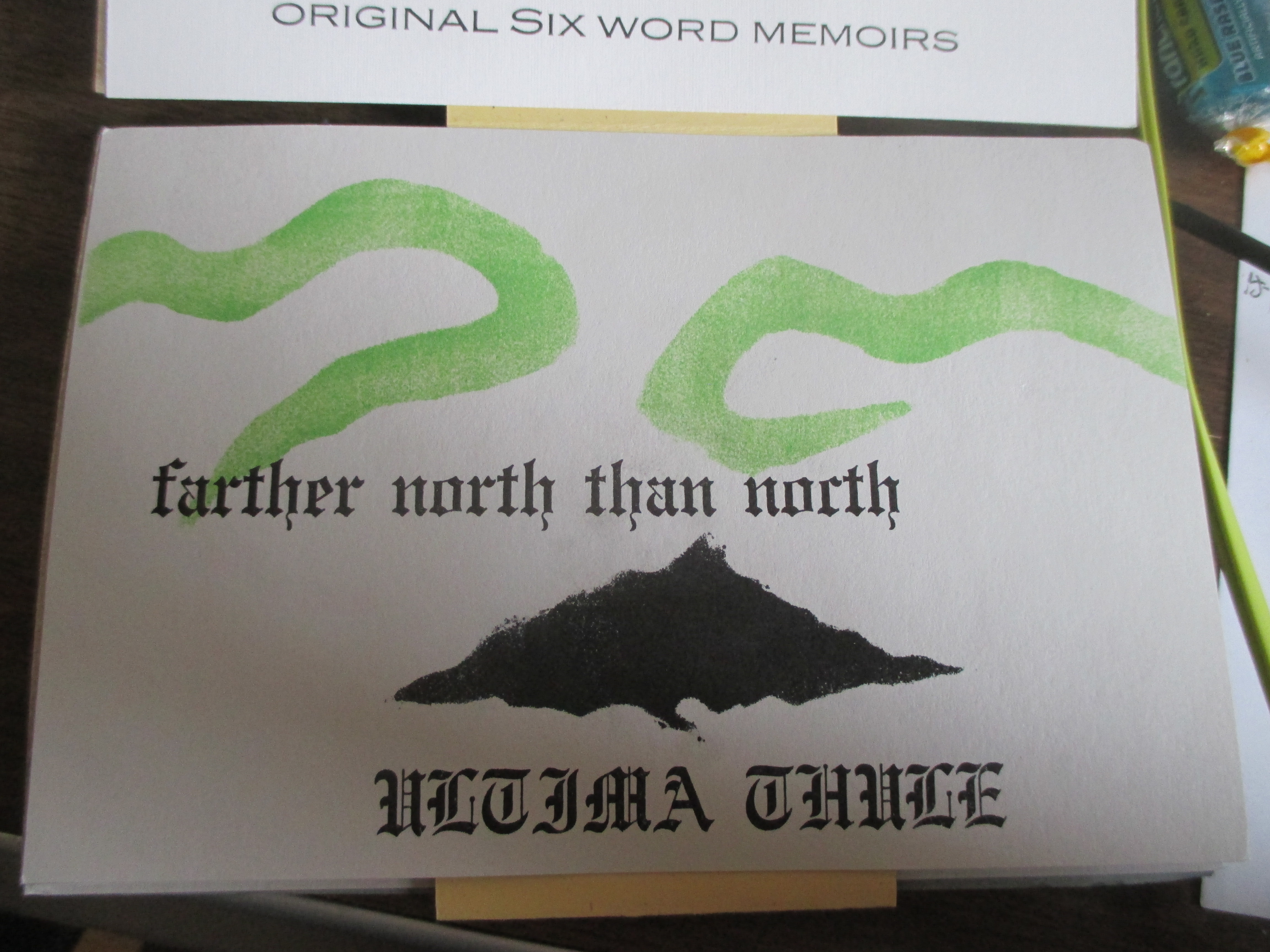

read histories of voyages to the poles, like Shackleton’s trips to the Antarctic, you learn that the closer you get to the edges of the world, the more surreal and terrifying things get.

read histories of voyages to the poles, like Shackleton’s trips to the Antarctic, you learn that the closer you get to the edges of the world, the more surreal and terrifying things get.

There was a tub near one standalone shelf, which was dedicated to FOLKLORE AND LEGENDS. That was my tub. A lot of Native American story collections, a lot of big fairy tale picture books. But the books that got me were Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark. I read those books over and over, burning the illustrations of Stephen Gammell deep into my unconscious, which is high on the APA’s list of predispositions for becoming a serial murderer later in life. Then I realized that I could tell these stories to other kids when I went to YCAMP.

There was a tub near one standalone shelf, which was dedicated to FOLKLORE AND LEGENDS. That was my tub. A lot of Native American story collections, a lot of big fairy tale picture books. But the books that got me were Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark. I read those books over and over, burning the illustrations of Stephen Gammell deep into my unconscious, which is high on the APA’s list of predispositions for becoming a serial murderer later in life. Then I realized that I could tell these stories to other kids when I went to YCAMP. remember standing in the shade of that big birch tree, surrounded by two semi-circles of kids who had forgotten about the heat. I would tell them about the tracks in the snow, the black pines, the silence and the cold, and the wind blowing through those big, black trees. Lying under a cot in a hunting lodge, one man would hear the roof lift off the eaves and see the big white claws of the Wendigo lift his friends out one by one, until he was alone. Then the roof would come back down, and the wind would blow away into the trees.

remember standing in the shade of that big birch tree, surrounded by two semi-circles of kids who had forgotten about the heat. I would tell them about the tracks in the snow, the black pines, the silence and the cold, and the wind blowing through those big, black trees. Lying under a cot in a hunting lodge, one man would hear the roof lift off the eaves and see the big white claws of the Wendigo lift his friends out one by one, until he was alone. Then the roof would come back down, and the wind would blow away into the trees.