I have a fascination with the metal buttons on pay phones, the pixels on old Zenith televisions, the writing on IV drip bags, and the lettering on manhole covers. I walk around New York with my hands running over metal railings and my eyes sweeping over the small details. Every stairway in the New York subway system has a letter and number designation written on a small plaque below one of the steps. Every restaurant in the city has a health rating in the window. And at the intersection of Madison and 30th Street is a Toynbee Tile.

Sometimes I sit on the wooden benches in the subway and imagine being the last man on Earth, confined to the island of Manhattan. I imagine crawling over every inch of it, studying a single patch of street asphalt with the same intensity as the Mona Lisa. There’s that scene in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, where Cameron is looking at A Sunday Afternoon on La Grand Jatte, and he keeps looking closer and closer at the little girl, and the camera keeps zooming in on her face until it’s nothing but a bunch of colored dots.

Art has low resolution. Life, on the other hand, has infinite resolution.

There is a school of writing that says your job as a writer, first and foremost, is to notice things. This is what I was taught. It’s the same school of thought that stresses concrete details in every line of your writing, so that every dimension of your story is vivid, tactile, textured, and beautifully, truthfully rendered. All those candy wrappers and weeds poking through the sidewalk are your material as a writer, because they evoke the realness of everyday life. And that’s your job as a writer: to render life as realistically as possible. And you learn to do that by noticing the small details.

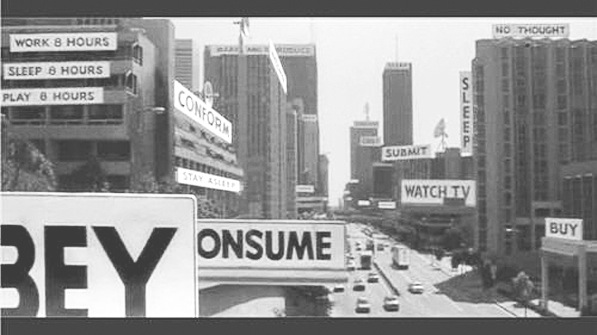

If you read American Psycho, 30% of the book is taken up in a meticulous catalogue of the colors, cuts, and brands of every character’s suit, tie, shoe, dress, cuff links and handkerchief. In fact, much of Patrick Bateman’s life seems to be taken up in the pursuit of an encyclopedic knowledge of style, fashion, and taste. This isn’t just because Patrick is a psychopath. It’s because all that matters in his social circles is the minutiae: the length of your coat sleeves, what you order at restaurants, and what kind of stereo you have. As you read, you begin to learn the language of affluence as if it’s a foreign culture, with Patrick as your guide. You get immersed in his world, his mindset, through the small details. So when the murders begin, they feel that much more surreal.

This kind of writing is based around the ideal of ‘verisimilitude,’ which is the appearance or quality of being real and believable. It’s what allows us to become immersed in a story, and, for a while, believe that it’s real. Many writers today do it by mining everyday life for those small, concrete details: smells, sights, textures. Those details immerse the reader in the story, and allow the illusion of fiction to happen.

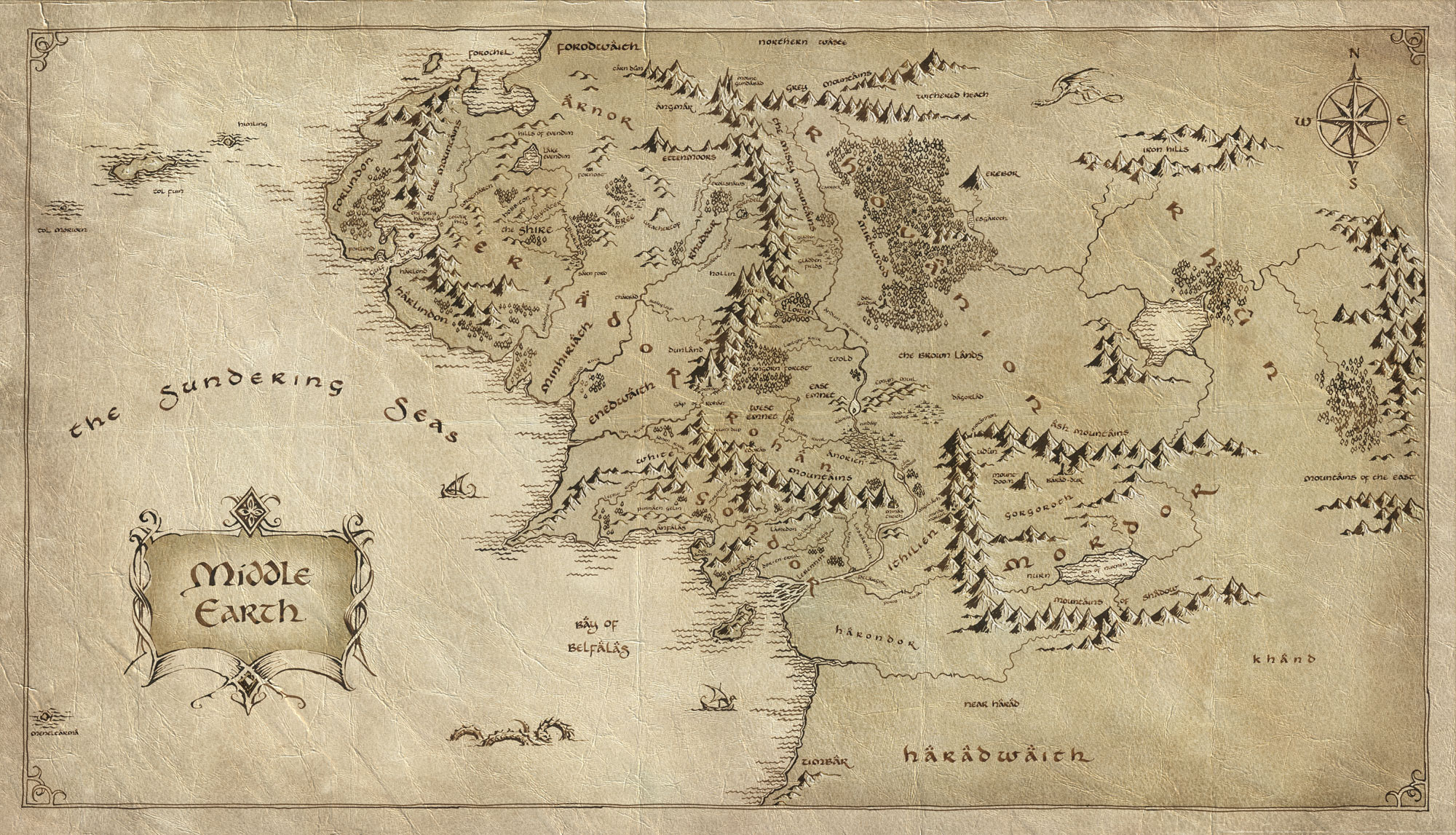

So imagine you’re telling a story in a time, place, and universe that doesn’t exist. Imagine you’re writing second-world fantasy.

Maybe now you can understand how fucked you are. You don’t get to immediately pull from a shared pool of experiences. You don’t get to see your world laid out in front of you every waking minute, in all its minute detail. No, instead you have to steal, jury-rig, and cut from whole cloth the sights, sounds, and textures that will immerse your readers.

Watch a weather forecast, look at a street map of your town, or pick up an English-to-French Dictionary, and you’ll realize how hard it is to make up a world from scratch, down to the smallest details. But the real world is a good jumping off point. Learn about Zoroaster, the Zen poet Basho, and the economic collapse of Detroit. Then begin to work your way down to the feeling of varnished wood on your fingertips as you run your hand over the ribs of a suit of samurai armor, which is called the do. Find out what the little recycling number is on your box of cereal, and what that means about its composition. Stay up all night and watch the sunrise alone, and remember how it felt.

I think to make a good secondary world you have to be a whole universe boiled into one person, but if you do it right, you’ll never stop learning. About the stars, about music, about human history—fantasy is about bringing back stories from the bounds of imagination, and writing it is your excuse to explore it. What you’ll find, I think, is that you will begin noticing the small details around you, the pay phones and manhole covers, and admiring them as works of art, just as much as Beowulf is. There’s beauty in the small details.

And I think the advice given to writers, oftentimes, is the same advice given to those who want to make the most out of their life. Kafka wasn’t very upbeat, but he was always telling people to chase the sublime, to dive into what they feared the most in order to uncover what they needed to live. And there’s a quote by someone, maybe Picasso, that every piece of art is a self-portrait. I think that makes sense for writing fantasy, because if you’re going to write it well, it’s going to be ingrained in the way you live and the way you look at things.

Still, people will ask why you spend so much time building worlds, cultures, and metaphysics for worlds that don’t exist. What’s the use of these stories, or fantasy at all? There’s a scene in Wizard of Earthsea, when Ged picks up a plant called fourfoil, and asks the mage Ogion what its use is. Ogion replies,

“When you know the fourfoil in all its seasons root and leaf and flower, by sight and scent and seed then you may learn its true name, knowing its being; which is more than its use. What, after all, is the use of you? Or of myself? Is Gont Mountain useful, or the Open Sea?”

I imagine kneeling down on a sidewalk in New York and picking up a sprig of fourfoil growing out of the seam between the cement and a building. There is no use for fourfoil, but in that moment, with fifty-story buildings looming all around me and planes flying overhead and dozens of people walking by me to get to a bar or Grand Central, I see a spark of another time, another place in its tiny leaves.

If I can immerse people in a story, what is the use of reality?