Welcome back to my ongoing series of posts on my game demo project “Black Heaven: a Necromantic Dating Sim”!

If you haven’t read part Part 1, go read that first, you animal.

This time, I’m talking about narrative—outlining the story, figuring out the characters, and writing the opening scene. Because Black Heaven is just a demo at this stage, there are only four scenes, each of which introduces the player to one of the key characters: the necromancer No-Eyes, the scholar Ru Okazi, the martial arts master Izagi Ito, and the conwoman Leathe. Still, putting together the demo meant having a general outline of the plot for the entire game, as well as in-depth outlines for the characters.

Plot and Setting

The first step in creating the game’s narrative was brainstorming the plot. After a few iterations on the general idea of collecting ghosts for a necromancer in a post-apocalyptic fantasy world, I came up with this summary:

Five years ago, a devastating plague spread across the world, driving humanity into the long-abandoned subterranean ruins known as the Starving Kingdoms. As one of the few survivors, you’ve been living a lonely existence, haunted by memories of the world you knew…until a necromancer named No-Eyes offers you a deal: if you bring him the ghosts of three people, he will bind one of them to you for eternity. However, the others will be trapped in his grimoire forever.

This summary was eventually adapted into the game’s overall description, but first and foremost it was a clear, concise encapsulation of the game’s setting, plot and conflict. I split it into four parts:

- Setting: post-apocalyptic fantasy world ravaged by a plague

- Plot:

- Desire: your character is lonely, and desires companionship

- Solution: you make a deal with a necromancer to obtain a ghost companion

- Conflict A: you must find and capture the ghosts, as well as convince one to become your companion

- Conflict B: if you fulfill your end of the deal, the other ghosts you collect will be doomed

Apart from the expected challenge of romancing one of the ghosts (Conflict A), I wanted there to be another conflict for the player to deal with, which was a moral dilemma that asked whether the player would sacrifice the souls of the other two ghosts they didn’t choose to romance (Conflict B). The moral implications of Conflict B eventually developed into a third secret, conflict, which I won’t go into detail here…

Setting

As for setting, I drew strong inspiration from the landscapes and worlds of Dark Souls and Bloodborne (the latter of which is also afflicted by a rampant plague). I liked the idea of exploring the ruins of a dark, subterranean city, and decided to set the game partly underground.

When it came to the worldbuilding aspects of the game, such as magic, metaphysics, and history, I drew on my own body of stories. One of the key elements I incorporated was “physiomancy,” the study of the human body with the goal of discovering a path to eternal life. The main character used to be a physiomancer, as were No-Eyes and Ru, and the study of immortality is woven into the origin of the plague that swept through the world.

Here are some of the visual references I used when imagining the world of the game (all are from the Dark Souls series or Bloodborne):

Characters

The first and most important character I figured out for the story was No-Eyes—he’s the primary “antagonist” and the person who gets the plot going. The player meets him while scavenging in a subterranean library, an encounter that serves as the intro to the game.

I decided to use a character profile format I’d picked up when I was interviewing at Gameloft, which included an occupation, personality, and key words. Here’s what No-Eyes’ character profile looked like:

NO-EYES

Key Appearance Traits: close-fitting black robes, smooth, eyeless helmet, gloves, no exposed skin, tall, emaciated

Occupation: Necromancer

Personality: No-Eyes is irreverent, outgoing, charismatic, highly intelligent, cynical, and entirely without morals. He sees other humans as amusements or puppets, and is highly adept at twisting them to his own ends.

Key words: relaxed, conniving, cruel, humorous

The other character profiles followed this same format—you can read all of them in the Art Brief.

One of the things I learned during my creative writing courses is to set up “trios” of characters: trios allow a writer to flesh out characters by making their traits opposed to one another, which “bakes in” the potential for conflict and tension. For the demo, I decided to introduce a distinct trio of potential romance interests:

- Ru, the shy scholar

- Izagi, the fierce martial artist

- Leathe, the shrewd conwoman

Each of these characters was designed to be easily and intuitively understood, but with a few hidden dimensions unique to each, which would come into play in their horror forms and relationships with the player.

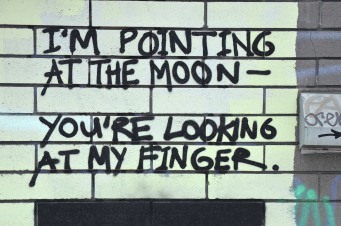

Of course, there’s already an avalanche of articles, charts, and memes exploring the very well-established archetypes of female romantic interests in anime, like this one:

I’m not a huge fan of this kind of pigeonholing, but I do understand that most characters end up falling into archetypes. Ru, for example, resembles Yuri from DDLC: shy, bookish girl who’s nervous around other people. No-Eyes resembles an archetypal Mephistopheles or “manipulative bastard.”

If Joseph Campbell has taught me anything, it’s that archetypes are a part of writing. It’s not a bad thing that a character is recognizable or familiar, but a writer needs to make their own mark on them to make them unique.

Working with Archetpyes and Creating Complex Characters

After thinking about conversation trees and how I would structure player interactions with the characters, I decided to take inspiration from Mass Effect‘s Paragon and Renegade elements. However, instead of a dichotomous ‘hero’ or ‘rogue’ option for each conversation, I created a three-option system, where each choice falls into one of the following attitudes and appeals to certain characters:

- Gentle (associated with Ru)

- Bold (associated with Izagi)

- Cunning (associated with Leathe and No-Eyes)

The more the player chooses a certain type of option (such as “Gentle”), the higher the disposition of the corresponding characters. However, though Izagi responds positively to the Bold options because her character’s ‘archetype’ is fierce and brash, her personality is more complicated than that.

One key idea I took from my writing courses is that complex, believable characters are built on contradictions. When I was designing the character of Leathe, for example, I wanted her to take pride in her ability to manipulate people, emotionally and physically—as a conwoman, she sees it as part of her craft, as well as proof that she’s smarter than other people. The contradiction is this: Leathe ends up getting tired of pretending to be someone she’s not, but is too afraid of expressing herself genuinely, which is something she associates with vulnerability.

These contradictions are present in each character, and end up branching out into smaller traits that define the character’s personality. If you want to read more about how this kind of characterization is employed in games, check out my piece on Mass Effect 2‘s infamous fight between Jack and Miranda.

Planning the Introduction Scene

Before writing out the introductory scene for the game, I made a list of the things I needed to introduce or establish:

- The main character’s connection to the character Ru (a former friend)

- The main character’s previous occupation as a physiomantic scholar

- The plague that effectively wiped out civilization

- Ru’s death

- The subterranean setting

- The way the player survives in the post-plague world (a filter mask)

- The player’s current location (the Library of Gizaron)

- The character of No-Eyes (including his background)

- The three conversation options/paths (Gentle, Bold, and Cunning)

- The deal between No-Eyes and the player

- Information about the ghost characters

- The beginning of the player’s quest

I decided to start with a horror-tinged dream sequence that introduced the plague and the player’s former relationship with Ru. Dream sequences aren’t exactly original, but done right, they can be surreal and horrifying, especially if the player isn’t sure if it’s the real opening of the game.

The dream is interrupted by an immediate threat: the player’s filter mask is clogged with ash and dust, suffocating them. From there, there’s some exposition and the player gets a chance to relax and take in the setting. Immediately after that, they encounter No-Eyes, who hasn’t seen them yet. The player must make a choice about how to approach him, which leads to the introduction to the three-path conversation system.

Outlining the Scene in Twine

When I first started the Twine outline for Black Heaven, I wanted it to be as complex and non-linear as possible in order to give the player a lot of agency. Each of the little squares below represents a text passage, and each of the lines connecting them represents a connection between two different passages, with an arrow showing which direction the narrative is flowing. Depending on the choices a player makes, their narrative path will be different.

As you can see, the map below has a pretty small number of text passages, but has a whole lot of connections:

Here’s a closer view of the story map, which shows how complicated and multidirectional the narrative can get. You’ll also notice that a big branch in the narrative happens at one passage: “Get Up Intro”. This was meant to be one of the key choice moments in the scene, and would cause the player to branch into one of the three routes based on how they handled the initial meeting with No-Eyes.

Unfortunately, this structure caused some pretty significant problems. Because the conversation could go so many different ways (and even cross over into different ‘routes’), each passage in the narrative had to be somewhat modular so it could fit together in many possible combinations. Though this modularity meant the player could get to the same place through multiple routes, it also meant the flow of the interactions between No-Eyes and the player came across as abrupt and choppy.

This caused a realization: the more player choice you allow, the less control you have over the unified effect of the narrative. It’s much more manageable (and impactful) if choices are restricted to a few key moments, rather than try to offer a hundred ultimately minor options that sacrifice quality for the illusion of freedom.

After a few revisions, the story map looked like this:

Notice how clearly defined the three routes are (top, middle, and bottom, joining together about halfway to the right), how many fewer lines cross between the routes, and how few lines there are in general. Though “linear storytelling” is usually a dirty word among gamers, writing this short scene showed me that it’s especially useful in the beginning of a game, when the writer is trying to establish the setting, characters, and situation. Here’s a closer look at the story map:

Conclusion to Part 2:

Like with Part 1, this covers a very small part of the work that went into the narrative aspect of the game—instead of diving into the minutiae, I’ve tried to hit the highlights and big ideas.

In Part 3, I’m going to cover my first interactions with the Ren’Py engine, including learning how to use Python and set up a scene.

You can play through the Introduction scene for “Black Heaven” on itch.io using Twine now! Keep in mind, it’s still a work-in-progress.

I first heard about this book when reading through Philip K. Dick’s biography,

I first heard about this book when reading through Philip K. Dick’s biography,  NON-FICTION: Zen Buddhism, Selected Writing of D.T. Suzuki, Edited by William Barrett

NON-FICTION: Zen Buddhism, Selected Writing of D.T. Suzuki, Edited by William Barrett NON-FICTION: A Burglar’s Guide to The City, by Geoff Manaugh

NON-FICTION: A Burglar’s Guide to The City, by Geoff Manaugh FICTION: Clarkesworld Year Six Anthology, Clarkesworld Magazine

FICTION: Clarkesworld Year Six Anthology, Clarkesworld Magazine MANGA: Opus, Satoshi Kon

MANGA: Opus, Satoshi Kon Wikipedia: Bagua

Wikipedia: Bagua The Five Animals in Martial Arts

The Five Animals in Martial Arts Luohan (Martial Arts)

Luohan (Martial Arts)

This past week I finished I Am Alive and You Are Dead, a biography of Philip K. Dick, the author of Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep (the inspiration for Blade Runner) and The Man in the High Castle. Dick won the Hugo Award in 1963, and ended up being the namesake of his own sci-fi award. I’d read Do Androids years ago, and it’s one of the few sci-fi novels whose ending made me cry.

This past week I finished I Am Alive and You Are Dead, a biography of Philip K. Dick, the author of Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep (the inspiration for Blade Runner) and The Man in the High Castle. Dick won the Hugo Award in 1963, and ended up being the namesake of his own sci-fi award. I’d read Do Androids years ago, and it’s one of the few sci-fi novels whose ending made me cry.