I first heard about this book when reading through Philip K. Dick’s biography, I Am Alive and You Are Dead, which took its title from one of the more chilling lines in Ubik. It seemed to have everything I could ever want: existential crises, meditations on eternity, entropy, and the human spirit, and a mind-bending journey through an illusory world created in the dying psyches of twelve people.

I first heard about this book when reading through Philip K. Dick’s biography, I Am Alive and You Are Dead, which took its title from one of the more chilling lines in Ubik. It seemed to have everything I could ever want: existential crises, meditations on eternity, entropy, and the human spirit, and a mind-bending journey through an illusory world created in the dying psyches of twelve people.

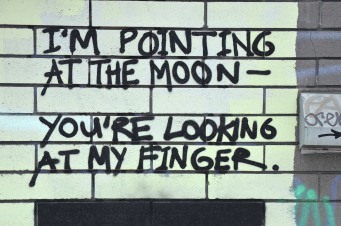

But Ubik reads more like a rushed draft and a splatter chart than “One of Time’s 100 Best English-language Novels,” as my edition claims. So many different rules and plot strands are set up (including Pat Conley’s time-reversion ability, Runciter’s manifestations, and the eponymous Ubik) that seem to hint at a single, mind-blowing explanation, but everything that is built up falls apart about 50 pages later. The effect isn’t, as The Guardian claims, a “squishy” novel that defies explanation and evokes the malleability of reality; the result is book that fails to function as a story, or even a comment on stories.

The front cover blurb from Rolling Stone sums up the disconnect, I think, between the people who see Ubik as an avant-garde masterpiece and people like me, who think it’s a goddamn mess: Phillip K. Dick is “The most brilliant SF mind on any planet.” It doesn’t say anything about being a good writer or storyteller. Books like Ubik can get away with being absolutely incoherent by claiming to deal with big ideas. For all its foibles and shortcomings, Ubik can still claim that its telling a sci-fi story that deals with telepathy, eternity, reality, and the nature of life and death, counting on the sheer weight of those ideas to make it worthwhile.

This is a tough claim to assault because a lot of really brilliant experiments in literature and art fail. You can argue hypertext fiction and House of Leaves failed at their attempts at revolutionizing the format of the novel, but their attempt inspired other writers and maybe some readers to reassess what a story can do. The ideas and concepts they brought to the table, like non-linearity, ergodic literature, and multi-media storytelling, have value, just as Ubik has value in exploring the concepts of reality, life, and entropy. Some passages really stuck out to me:

“One invisible puff-puff whisk of economically priced Ubik banishes compulsive obsessive fears that the entire world is turning into clotted milk, worn-out tape recorders and obsolete iron-cage elevators, plus other, further, as-yet-unglimpsed manifestations of decay.

This is the same looming horror at entropy that was embodied in “kipple” in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep. This passage sums up the apocalyptic, reality-destroying horror that waits for Joe Chip and his friends, evoked in the material decay of everything around them: milk, tape recorders, even elevators.

“But the old theory–didn’t Plato think that something survived the decline, something inner not able to decay? Maybe so, he thought. To be reborn again, as the Tibetan Book of the Dead says…Because in that case, we all can meet again. In, as in Winnie the Pooh, another part of the forest, where a boy and his bear will always be playing…a category, he though, imperishable. Like all of us. We will all wind up with Pooh, in a clearer, more durable new place.”

This reminds me of the poem Heaven by Patrick Phillips. It’s a surprisingly tender image of an afterlife, apart from all decay and the reality we know. It’s transcendental in the deepest sense of the word.

But none of it counterbalances the seemingly haphazard, half-baked, and frustrating plotting in the book. Good ideas might be able to salvage a badly written book in the eyes of critics and literary theorists, but no amount of avant-garde cred can make Ubik a passable read. The best experimental writers, the ones that deserve the highest praise, learn how to violate the rules of narrative and meaning within their stories and create a piece of fiction that has its own logic and its own intuitive way of reading it, like a dream.

Phillip K. Dick doesn’t accomplish this in Ubik. He sets up a world with a number of rules, but discards them one after another, until he discards everything. So there’s nothing to talk about and nothing to read in Ubik except its profound ideas and its profound failures. There’s no “vivid and continuous dream,” as John Gardner called it. So ironically enough, Ubik, a book about being immersed in a dream world that can’t be distinguished from reality, never tricked me into forgetting, even for a moment, that it was anything more than a bunch of words on a page, written by a man named Philip K. Dick.

THE Three Body Problem by Cixin Liu

THE Three Body Problem by Cixin Liu 7 Different Ways Fantasy Has Used Language as Magic

7 Different Ways Fantasy Has Used Language as Magic No Mother Tongue: Language in the world of Magic

No Mother Tongue: Language in the world of Magic

The Elements of Murder by John EmsLEY

The Elements of Murder by John EmsLEY An Incomplete History of the Art of Funerary Violin By Rohan Kriawaczek

An Incomplete History of the Art of Funerary Violin By Rohan Kriawaczek

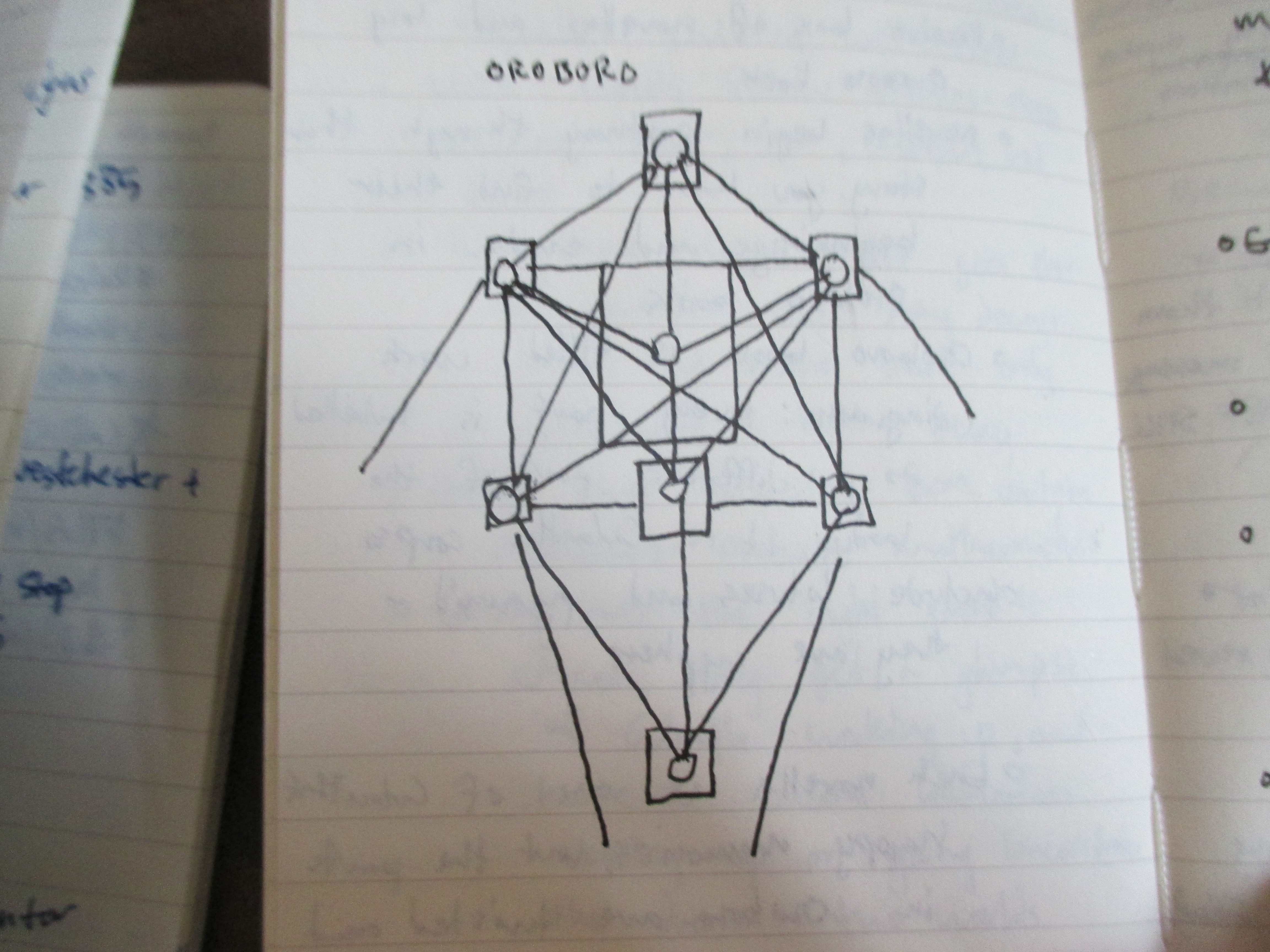

Cicada 3301 is my new obsession. Combining cryptography, anonymity, and strange ARG puzzles with mysticism and occult trappings, these bastards are probably the real-life

Cicada 3301 is my new obsession. Combining cryptography, anonymity, and strange ARG puzzles with mysticism and occult trappings, these bastards are probably the real-life  NON-FICTION: Zen Buddhism, Selected Writing of D.T. Suzuki, Edited by William Barrett

NON-FICTION: Zen Buddhism, Selected Writing of D.T. Suzuki, Edited by William Barrett NON-FICTION: A Burglar’s Guide to The City, by Geoff Manaugh

NON-FICTION: A Burglar’s Guide to The City, by Geoff Manaugh FICTION: Clarkesworld Year Six Anthology, Clarkesworld Magazine

FICTION: Clarkesworld Year Six Anthology, Clarkesworld Magazine MANGA: Opus, Satoshi Kon

MANGA: Opus, Satoshi Kon Wikipedia: Bagua

Wikipedia: Bagua The Five Animals in Martial Arts

The Five Animals in Martial Arts Luohan (Martial Arts)

Luohan (Martial Arts)

This past week I finished I Am Alive and You Are Dead, a biography of Philip K. Dick, the author of Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep (the inspiration for Blade Runner) and The Man in the High Castle. Dick won the Hugo Award in 1963, and ended up being the namesake of his own sci-fi award. I’d read Do Androids years ago, and it’s one of the few sci-fi novels whose ending made me cry.

This past week I finished I Am Alive and You Are Dead, a biography of Philip K. Dick, the author of Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep (the inspiration for Blade Runner) and The Man in the High Castle. Dick won the Hugo Award in 1963, and ended up being the namesake of his own sci-fi award. I’d read Do Androids years ago, and it’s one of the few sci-fi novels whose ending made me cry.

pieces of metanarrative, but Johnny Truant’s invasive footnotes, evocative of someone else’s mind invading the story, had no substance to them, nothing that fit together with the dry scholarly passages about the Navidson Record and the drama of the expeditions into the heart of the house. And that’s my main critique of most of the book: these fantastic, inventive typographical tricks didn’t come together as a cohesive whole to evoke the story it was telling. Instead, it ended up as mostly white noise, a bunch of jigsaw pieces glued onto a very compelling nucleus, the house, whose borders and boundaries can’t be contained in space, time, or (potentially) the book itself.

pieces of metanarrative, but Johnny Truant’s invasive footnotes, evocative of someone else’s mind invading the story, had no substance to them, nothing that fit together with the dry scholarly passages about the Navidson Record and the drama of the expeditions into the heart of the house. And that’s my main critique of most of the book: these fantastic, inventive typographical tricks didn’t come together as a cohesive whole to evoke the story it was telling. Instead, it ended up as mostly white noise, a bunch of jigsaw pieces glued onto a very compelling nucleus, the house, whose borders and boundaries can’t be contained in space, time, or (potentially) the book itself. A good counterexample of a piece of experimental literature that did its job well is Trillium, the graphic novel with Jeff Lemire. It takes a lot of skill to make a reader just flip a book upside down, but Trillium gave an amazing narrative reason to do just that: at one point in the book, the narrative splits into two parallel universes, and so the panels are actually running parallel to one another, but flipped so you don’t read both timelines at once. This makes you focus on one at a time while also getting little peripheral glimpses of what’s to come. It’s genius, and it works because it’s coherent, intuitive to navigate, and grounded in the narrative. You know why it’s happening, how to read it, and what it means for the story.

A good counterexample of a piece of experimental literature that did its job well is Trillium, the graphic novel with Jeff Lemire. It takes a lot of skill to make a reader just flip a book upside down, but Trillium gave an amazing narrative reason to do just that: at one point in the book, the narrative splits into two parallel universes, and so the panels are actually running parallel to one another, but flipped so you don’t read both timelines at once. This makes you focus on one at a time while also getting little peripheral glimpses of what’s to come. It’s genius, and it works because it’s coherent, intuitive to navigate, and grounded in the narrative. You know why it’s happening, how to read it, and what it means for the story.

Let me put something in perspective.

Let me put something in perspective.

Nobody needs me to say that Cryptonomicon is relentlessly witty, written with wonderful, vivid prose, immersed in layers of fascinating concepts and technology, and absolutely vertigo-inducing in scope. These are all the elements that kept me coming back, despite the book having a page count higher than War and Peace. I just wish that there had been a plot to hold all of it up and make it into a coherent story, rather than a series of interesting digressions.

Nobody needs me to say that Cryptonomicon is relentlessly witty, written with wonderful, vivid prose, immersed in layers of fascinating concepts and technology, and absolutely vertigo-inducing in scope. These are all the elements that kept me coming back, despite the book having a page count higher than War and Peace. I just wish that there had been a plot to hold all of it up and make it into a coherent story, rather than a series of interesting digressions.