When I first heard about House of Leaves, I was excited. People told me it was maddening, mind-bending, the kind of thing meant to unhinge you from reality, using everything from metanarratives to typography to convey the insanity of its eponymous house. The book was meant to be a labyrinthine book about labyrinths, a story whose format was part of the narrative. That idea, that the form of a story could be part of the story, a kind of origami flower that opened as you read it, opened up new horizons in my imagination.

Then I sat down and read House of Leaves.

I couldn’t finish it. There was typographical trickery galore and some really tremendous  pieces of metanarrative, but Johnny Truant’s invasive footnotes, evocative of someone else’s mind invading the story, had no substance to them, nothing that fit together with the dry scholarly passages about the Navidson Record and the drama of the expeditions into the heart of the house. And that’s my main critique of most of the book: these fantastic, inventive typographical tricks didn’t come together as a cohesive whole to evoke the story it was telling. Instead, it ended up as mostly white noise, a bunch of jigsaw pieces glued onto a very compelling nucleus, the house, whose borders and boundaries can’t be contained in space, time, or (potentially) the book itself.

pieces of metanarrative, but Johnny Truant’s invasive footnotes, evocative of someone else’s mind invading the story, had no substance to them, nothing that fit together with the dry scholarly passages about the Navidson Record and the drama of the expeditions into the heart of the house. And that’s my main critique of most of the book: these fantastic, inventive typographical tricks didn’t come together as a cohesive whole to evoke the story it was telling. Instead, it ended up as mostly white noise, a bunch of jigsaw pieces glued onto a very compelling nucleus, the house, whose borders and boundaries can’t be contained in space, time, or (potentially) the book itself.

In the end, what made me put down the book was sheer disinterest. It hurts the narrative flow to include the kind of ergodic lit puzzles that House of Leaves throws out: reading upside-down and slantways, combing through footnotes and inlaid text boxes, reading pages with only one word on them, following margin-notes (ala Ship of Theseus). But I would gladly read a book that uses all the same tricks as long as I felt like it was all adding up to something. I didn’t give a fuck about Johnny Truant and his drug-fueled casual sex episodes. About halfway through the book, I realized that all these strands were a mess, not a tapestry, and it sucked my resolve to keep navigating all the puzzles.

A good counterexample of a piece of experimental literature that did its job well is Trillium, the graphic novel with Jeff Lemire. It takes a lot of skill to make a reader just flip a book upside down, but Trillium gave an amazing narrative reason to do just that: at one point in the book, the narrative splits into two parallel universes, and so the panels are actually running parallel to one another, but flipped so you don’t read both timelines at once. This makes you focus on one at a time while also getting little peripheral glimpses of what’s to come. It’s genius, and it works because it’s coherent, intuitive to navigate, and grounded in the narrative. You know why it’s happening, how to read it, and what it means for the story.

A good counterexample of a piece of experimental literature that did its job well is Trillium, the graphic novel with Jeff Lemire. It takes a lot of skill to make a reader just flip a book upside down, but Trillium gave an amazing narrative reason to do just that: at one point in the book, the narrative splits into two parallel universes, and so the panels are actually running parallel to one another, but flipped so you don’t read both timelines at once. This makes you focus on one at a time while also getting little peripheral glimpses of what’s to come. It’s genius, and it works because it’s coherent, intuitive to navigate, and grounded in the narrative. You know why it’s happening, how to read it, and what it means for the story.

House of Leaves may read like Harry Plinkett’s jigsaw puzzle challenge, but it still did something original and tremendously thought-provoking by giving an idea of what ergodic literature could do and be. The very idea of it inspires me, and despite the frustrations and disillusionment, I wanted to do something like it. But there were three things to keep in mind if I was going to fool around with ergodic literature:

- The structure and format of the story would have to be grounded in the story

- The way the reader navigates or decodes the text would have to be intuitive and immersive, meaning that it was easy to grasp and brought people deeper into the story

- The structure and format needed to have a good flow, making it easy to jump in and out of

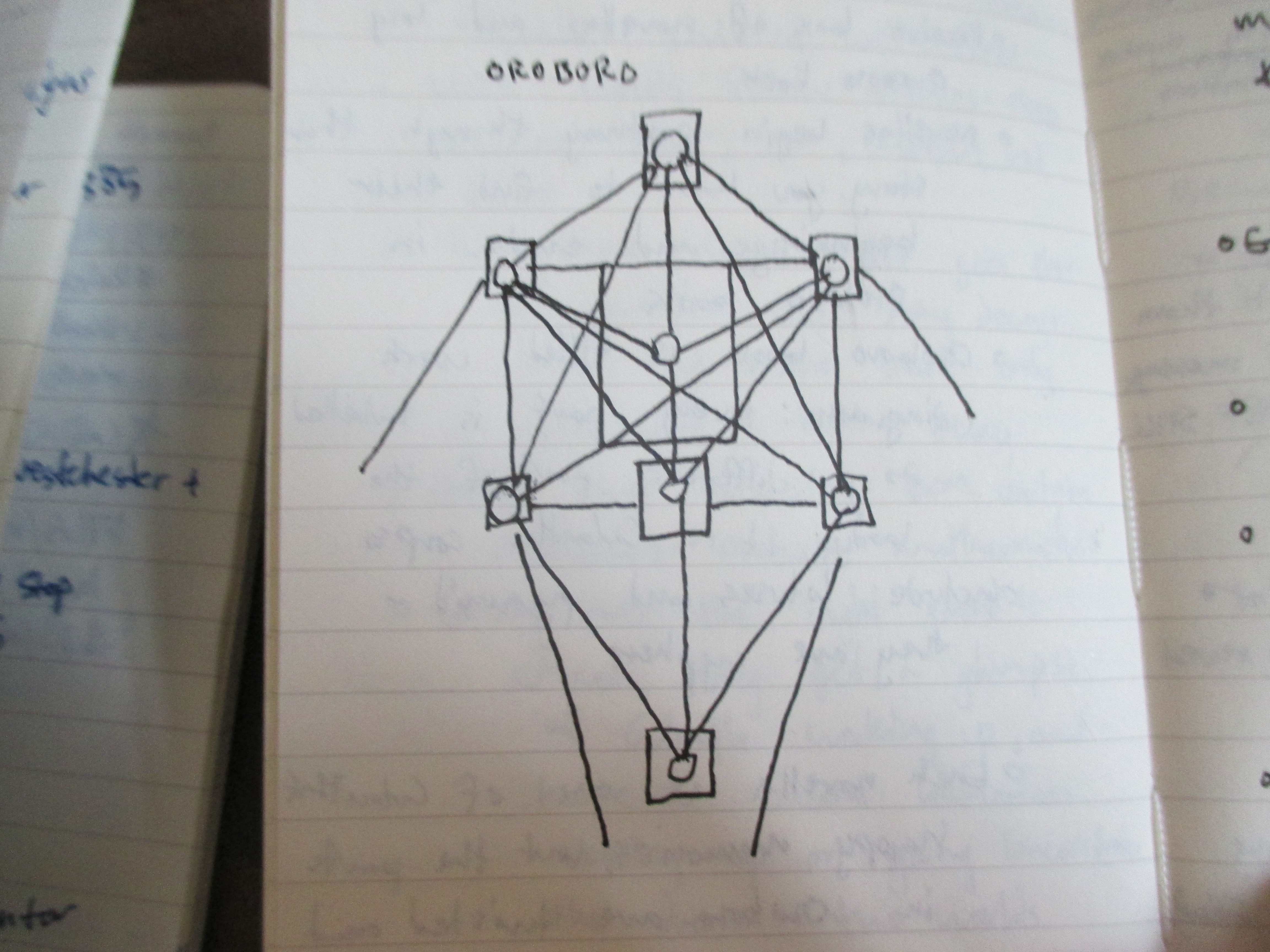

I came up with the idea of a “corpse” book, a story that was physically split into six separate books, like a torso with the limbs severed off. It would be, in practice, a constellation of short stories that illuminate a central novel, all united by invisible threads. You would start with all of the books, beginning by reading the central book, the torso, but periodically follow the narrative into one of the other limb books, then return. Each of the limbs would shed more light on the central book, but would be its own contained story and narrative.

The idea? Create a story about immortality, truth, and godhood whose structure and interconnections would mirror the Kabbalah Tree of Life and the Sephiroth, and whose story has to be unlocked like Hellraiser’s puzzle box, one piece at a time.

To be continued…

Let me put something in perspective.

Let me put something in perspective.

Nobody needs me to say that Cryptonomicon is relentlessly witty, written with wonderful, vivid prose, immersed in layers of fascinating concepts and technology, and absolutely vertigo-inducing in scope. These are all the elements that kept me coming back, despite the book having a page count higher than War and Peace. I just wish that there had been a plot to hold all of it up and make it into a coherent story, rather than a series of interesting digressions.

Nobody needs me to say that Cryptonomicon is relentlessly witty, written with wonderful, vivid prose, immersed in layers of fascinating concepts and technology, and absolutely vertigo-inducing in scope. These are all the elements that kept me coming back, despite the book having a page count higher than War and Peace. I just wish that there had been a plot to hold all of it up and make it into a coherent story, rather than a series of interesting digressions.