Have you ever heard of Ultima Thule? It was supposed to be an island up in the farthest, coldest reaches of the world, but because cartography back in the Age of Exploration was a lot of alcohol and making shit up, “Ultima Thule” eventually became a name for any place that was unchartable, unreachable. Sea exploration was special that way—there was a sense that, maybe, the world had no borders at all, and things just kept going. Mapping the ocean was mapping the boundaries of everything, and if you  read histories of voyages to the poles, like Shackleton’s trips to the Antarctic, you learn that the closer you get to the edges of the world, the more surreal and terrifying things get.

read histories of voyages to the poles, like Shackleton’s trips to the Antarctic, you learn that the closer you get to the edges of the world, the more surreal and terrifying things get.

A great example is sea ice: out near the Arctic, there’s something called ‘the Devil’s symphony,” the weird combination of crashes, whines, whistling, screeches and wobbles that the sea ice makes when its warped and compressed. There’s nothing in the world that sounds like it. There’s the aurora borealis out at the far latitudes, too, and the midnight sun and months of darkness. This is the stuff of legends. I was fascinated by the idea of an island out there, where the world stopped making sense. H.P. Lovecraft was enamored with the Antarctic as a kid, and his story “At the Mountains of Madness” is as much about wonder and insanity as it is about exploration.

One of the classes I took in college was Art of the Book. In it, you learned to make books like they did in the old days: with an awl, a bone folder, a handful of picas, and some hard liquor. We had a real Gutenberg printing press and a Bi Sheng press, the latter of which predates Gutenberg’s design by a couple hundred years. We also had drawers and drawers and drawers and drawers of tiny, metallic type, which we had to assemble into words by hand, then keep between metal slats, called slugs. God help you if you pancaked a drawer of type, ie dropped one butter-side down.

One of the first projects I did in Art of the Book, and one the proto-projects of the Occult Triangle Lab, was a postcard from Ultima Thule. I sketched out some thumbnails and settled on two designs: the island and the aurora, with the words FARTHER NORTH THAN NORTH—ULTIMA THULE. I set the type, inked it, and pressed it on our proofing roller, then cut a stencil out from plastic with a hotpoint gun. The final design looked like this:

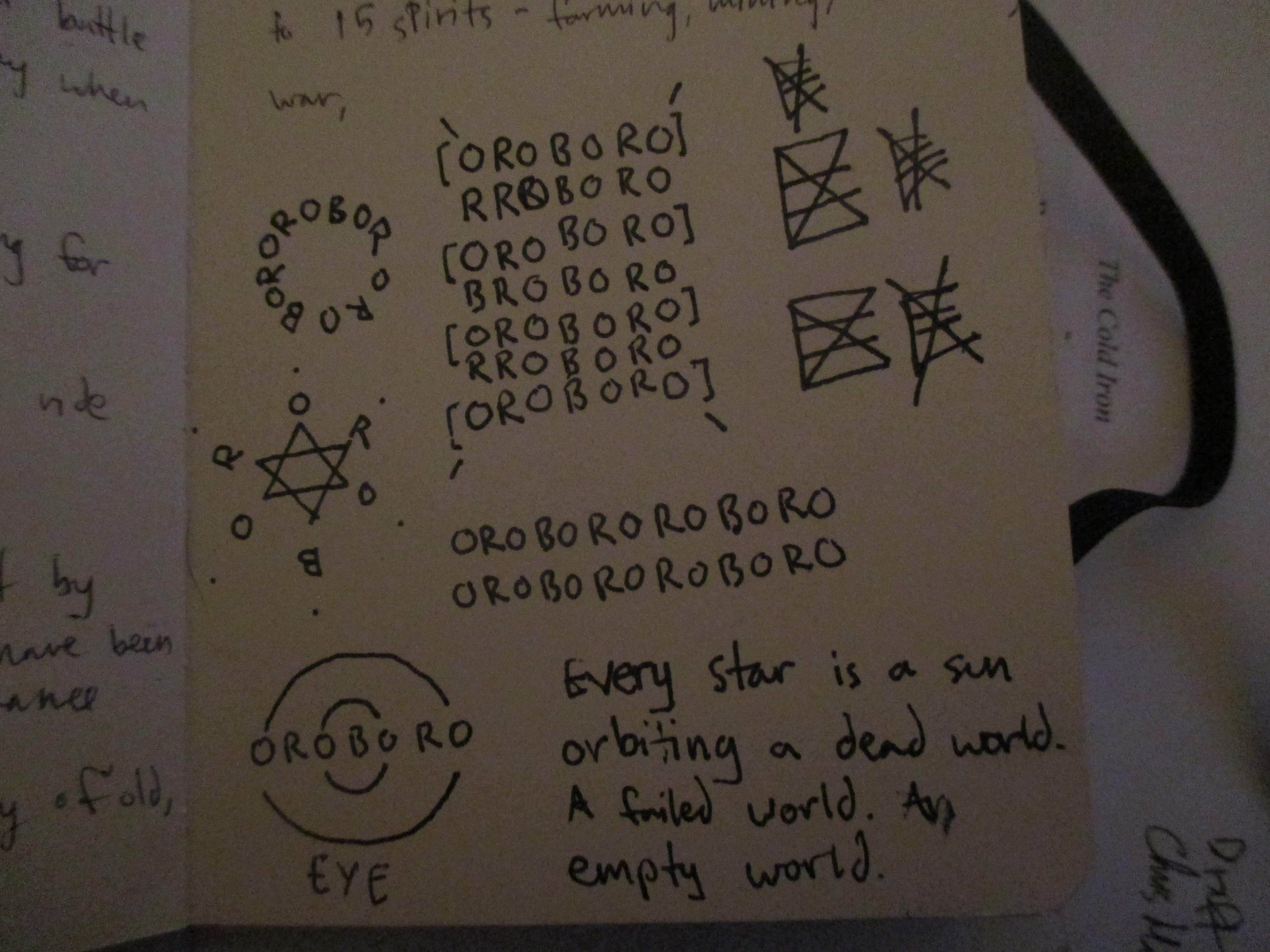

I ended up writing a story called The Voyage of the Sin-Edad, a short fantasy piece about a wizard and a group of sailors heading into the far north to find an island like Thule. That story inspired the next set of projects in Art of the Book: artifacts from the voyage. These included a hard-bound, water-soaked captain’s log ( I actually let the thing soak in a sink full of water), a Japanese stab-bound book of poetry carried by one of the characters, and a small, folded, triangular map that showed the drift of icebergs and the Sin-Edad’s course (the small pocketbook sketch at the top of the post is an early draft of the map).

These were the proto-projects, the incunabula of the Occult Triangle Lab, but they were based in the same veins that the Lab would eventually draw from: myth, origami, and storytelling. People in my Art of the Book class really enjoyed the artifacts and the story behind them, so I decided that I should make more. In time, Art of the Book became the catalyst for the Lab.

What made the Ultima Thule projects so interesting, I think, was the image of people treading into a world that was a lot older and vaster than humans. Last year, archaeologists found the remains of the HMS Erebus, one of the ships that belonged to the lost Franklin Expedition to the Arctic. Ever since the first corpses were found in a rowboat on the coast of King William Island, people have been trying to piece together what happened to the sailors. Some have been uncovered scattered across the ice, their bones carrying massive amounts of lead, and mounds of stones containing messages from the sailors, recording the dates that they abandoned their ships in the ice, were discovered in 1859. The Inuits have stories about them, saying that they watched the crew die as they walked, and that they had found skeletons with all the flesh sawed off, evidence of cannibalism. As far as anyone can tell, every member of the expedition died out there on the edge of the world.

Click the circular button below to Share.

There was a tub near one standalone shelf, which was dedicated to FOLKLORE AND LEGENDS. That was my tub. A lot of Native American story collections, a lot of big fairy tale picture books. But the books that got me were Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark. I read those books over and over, burning the illustrations of Stephen Gammell deep into my unconscious, which is high on the APA’s list of predispositions for becoming a serial murderer later in life. Then I realized that I could tell these stories to other kids when I went to YCAMP.

There was a tub near one standalone shelf, which was dedicated to FOLKLORE AND LEGENDS. That was my tub. A lot of Native American story collections, a lot of big fairy tale picture books. But the books that got me were Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark. I read those books over and over, burning the illustrations of Stephen Gammell deep into my unconscious, which is high on the APA’s list of predispositions for becoming a serial murderer later in life. Then I realized that I could tell these stories to other kids when I went to YCAMP. remember standing in the shade of that big birch tree, surrounded by two semi-circles of kids who had forgotten about the heat. I would tell them about the tracks in the snow, the black pines, the silence and the cold, and the wind blowing through those big, black trees. Lying under a cot in a hunting lodge, one man would hear the roof lift off the eaves and see the big white claws of the Wendigo lift his friends out one by one, until he was alone. Then the roof would come back down, and the wind would blow away into the trees.

remember standing in the shade of that big birch tree, surrounded by two semi-circles of kids who had forgotten about the heat. I would tell them about the tracks in the snow, the black pines, the silence and the cold, and the wind blowing through those big, black trees. Lying under a cot in a hunting lodge, one man would hear the roof lift off the eaves and see the big white claws of the Wendigo lift his friends out one by one, until he was alone. Then the roof would come back down, and the wind would blow away into the trees.